Bringing poetry to the people

Fall 2016 issue

Poetry elicits a visceral reaction in many people. The memories of a grade school classroom are often not fond. It’s common to outright hate poetry — an art form that seems to be known mainly for its games and trickery.

But what if poetry was never meant to fool?

There’s a fearless group of Calgary writers fighting to drag the much-maligned craft of poetry away from the stigma that is firmly attached to it. They want to bring poetry back to the people, where they insist it really belongs. Because regular people create poetry and they write it to share with you.

Micheline Maylor

English professor and 2016-2018 City of Calgary Poet Laureate

How poetry became uncool

Being a poet can seem like a strange life choice.

“It’s not a very well-defined sort of thing,” says Micheline Maylor, PhD and English professor at Mount Royal and the City of Calgary’s 2016-2018 Poet Laureate. “People think that poets are a bunch of flakes doing soft art and lamenting all things by candlelight in perpetual woe.”

It wasn’t always like this, though. Poetry used to be a way to communicate emotions better, not worse, than regular language, and was widely respected as a legitimate — and difficult — art form. Richard Harrison, professor of English at Mount Royal, says every century or so there is a backlash against the traditional concept of poetry by both writers and readers alike. Poets are known to deny their own profession, attempting to define it as something else.

Although the British-Canadian poet Robert W. Service was a virtual rock star in his day, “At his time, he hated poetry so much that he refused to call his own work ‘poetry,’” Harrison says. “He wrote ‘verse.’”

In a more contemporary setting, the rise of dub, rap and spoken word later in the 20th century was yet another rejection of sorts. Writers did everything they could to avoid the dry, intellectual privilege perceived in old-fashioned “page poetry,” and rejuvenate the poetic form through emphasis on how the poem sounds and what it says openly, says Harrison. These forms allowed poetry to become more raw, cutting and real … even perverse and alarming, even though it was often not recognized as poetry at all.

Some scholars think this counterattack happened because of the conventional methods of teaching poetry, which insisted on studying a poem by reading it for what it “really means” despite how it impacts its readers.

“There is a crushing need to interpret poetry,” says Harrison. “The people who don’t like poetry think they don’t understand it. And unfortunately it’s been used as an intelligence test.”

The manipulation of the poem can be said to coincide with what Harrison refers to as “cultural loyalty” created through language. It is the feeling that no matter what political or social connections we have, who we are is most intimately connected to how we speak and read.

“If you can only think in English, then in some sense, no matter where you are born, English is your home. That's ‘cultural loyalty,’” says Harrison.

Colonists from Britain knew that a standardized language would play in their favour and set up schools in English wherever they went. It is the classic pattern of an empire, where a national language that is taught and learned “properly” has the effect of creating an innate similarity and understanding of a culture and a political body.

This is what happened with poetry. Instead of being as simple as words describing something, an emotion or a thought, through no fault of its own, poetry became mired in politics.

To reduce the poem to a single, consensus meaning is to take away the very essence of what a poem is supposed to be, says Harrison. In the demand that a poem become something else through the power of Sherlock Holmes-esque deduction, the poem itself ceases to be important.

“Any kind of creation with words on a page or words in the sky, words on a screen, any one of those things is poetry,” he says. “Why can’t you just put words on a page and give people an experience? That is the meaning. That is the reason.

“The poem has always existed in the tension between what it is and what it means. We need to keep both.”

Harrison describes the habit of translating poems into one sentence, meaning or interpretation as doing violence to the poem and people responding to it.

Failure to “get” a poem makes people feel powerless, stupid. And you can’t persuade somebody something is good, or worth it, or enjoyable, if their experience of it is exclusionary, explains Harrison.

Mount Royal English professor derek beaulieu, PhD, who served as the 2014-2016 City of Calgary Poet Laureate, agrees with this standpoint.

“We are so afraid of poetry. We’ve been taught that it’s boring, that it’s dull, that it’s scary and something to be avoided so pervasively that when we are asked to write a poem, what we put out is so distant from ourselves,” says beaulieu.

He believes the way our students are taught in grade school has done them a bit of a disservice.

“One of the things that I try to throw away right away in the classroom is that there is no deep inner meaning in poetry. Read the words on the page. That’s it. Done. Nothing further than that. Read the words on the page and tell me what they mean to you,” beaulieu says.

He observes how some students tend to write flowery verse with rhyme and metre, which isn’t reflective of their actual real lives.

“It’s because we’re taught that poetry is frozen in amber like a prehistoric mosquito. No! Write me a love poem to your Pikachu. Write me something that is about what you are doing in the language of how you are doing it. But write today. In the way that you experience the world,” he says.

“Don’t try to write me a poem with all of that cultural baggage.”

pop-up poetry

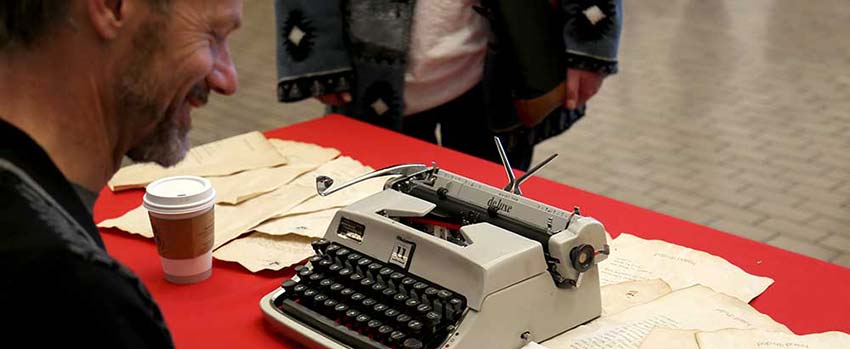

Drawn by the recognizable sound of typewriters and the unexpected spectacle of poets writing out loud, on Aug. 9 more than 100 people were treated to a personal poem on a topic of their choosing in downtown Calgary. The event, dubbed “Pop-Up Poetry,” was Mount Royal’s way of bringing poetry back to the people … both physically and literally.

The City of Calgary’s Poet Laureate and Mount Royal professor Micheline Maylor, along with a trio of her talented colleagues, fellow Mount Royal faculty members and well-known local poets Richard Harrison and derek beaulieu (Calgary’s 2014-2016 Poet Laureate), as well as storyteller Cassy Welburn, churned out dozens of poems each using words tossed at them from interested passersby.

Verse was created about coffee, fajitas and shoe leather. Loved ones were a popular muse. Dogs, too. Love, summer and the ocean also made up a few of the topics.

“Each of these spontaneous poems offered a tiny window into the minds of Calgarians,” said Maylor.

“Some of the requests were deeply personal. Others were kooky."

“In every case, it was a tremendous honour to tell stories through this medium and to share this art form with the downtown community.”

The event was intended to humanize the written word by putting writers directly in front of the folks reading their words.

“The idea of reaching out to the public to make poetry more integrated makes it something normal, something real and something that’s part of our community,” says beaulieu.

Update — Nov. 29, 2016

Mount Royal University staged another Pop-Up Poetry event on Main Street on Nov. 28, where 100 folks from the university community received a poem penned just for them. The writers were MRU professors derek beaulieu, Kit Dobson, Beth Everest, Richard Harrison and Micheline Maylor, and creative writing students also tried their hand at creating poetry under pressure. Keep your eyes and ears open, MRU's poets can "pop-up" at any time!

Where is poetry today?

According to Maylor, many people don’t realize that poetry already invades their lives daily, through music, songwriting, rap, visual arts and even in advertising.

“Poetry shows up in unexpected places all the time. It’s a matter of paying close attention, seeing that poetry is both an ad jingle and the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. That it is a genre big enough for Kanye and the Song of Solomon,” Maylor says.

beaulieu thinks that poetry is also perhaps the most perceptive of the art forms.

“It is responsive to the dialogue that we have with ourselves, with our community, with our surroundings,” beaulieu says. “Poets all respond to our world. We all respond to what’s around us and our concerns and our worries.”

David Hyttenrauch, PhD and chair of Mount Royal’s Department of English, Languages, and Cultures says, “There’s a tension in poetry to express the complexity of the human experience inventively and concisely. So it requires fearless examination, lateral thinking and precision with language (and sometimes with form). That’s a state of mind with value beyond poetry: it’s a means of getting to the essence of a problem, of self-examining and living fully and well.”

Going into his second year at Mount Royal, English major Gabriel Merencilla has been writing poetry on and off since about Grade 4. He writes when he’s inspired by an event or experience, and is refreshingly free of any sort of bias that may have stopped him from experimenting with language.

“I think a big part of poetry is just to express what we think onto paper. Because a lot of the time it’s not even about what we think, it’s about how we feel, and sometimes it’s so hard to translate that,” says Merencilla.

On Being Asked to Defend the B.A. with a Poem

Do I believe in it? Beyond it being, you know, my job?

It worked for me. I ate well from the spoon,

but I knew nothing about how knowledge was made, how

people who lives Statistics or Chemistry, Psychology,

or Business or Math talked, or thought, or what

jokes they made. Best thing I was told about growing up

was this: "There are two things to find out:

where you're going and who's going with you.

Take them in that order," and

I had no idea who my people would be--

but when I went to university, I never thought they'd be poets.

Or English profs. But that's what it's about:

thinking you know yourself, then finding out you don't,

being confused about the big things and the small,

and pressured into grace;

learning how to be patient at what you're not yet good at,

and how to deal with the weight of what you are.

Since they asked me to write this, I've been playing

with those initials, "B.A." It means "Bachelor of Arts"of course,

So I've been thinking, these are the letters that tell you

I've finished what I started. And it changed me;

they are the letters at the beginningand the end

of what I worked hard at so I could grow. They are

the end of who I was, and the beginning of who I've been

ever since. They are the initials of my Before and my After.

Do I believe in this for you?

Beyond it being, as I've said, my job?

Yes. And the relationship is the reverse:

It's my job because I believe in it -- and you.

What is poetry capable of?

Poetry is words on a page, yes, but it is also much more than that. Maylor describes it as the “great connector.”

“Poetry is the way that we express when we feel something. When feeling love, or reverence, or fear, that feeling comes unnamed or unworded. And I think that poetry is a very human attempt to put into words the very wordless feelings of being human,” says Maylor.

There’s power in poetry. Words are a way of giving freely, and a good poem is uncompromising and brave.

“Poetry can do whatever you want it to do. Poetry is not something to be feared. Poetry should be the charged and thoughtful use of language and its particles. Have it evoke. Have it create something that you didn’t expect. That’s what we look for in poetry,” says beaulieu.

Poetry in Calgary

In the creation of the Poet Laureate program, Calgary’s Mayor Naheed Nenshi has come out as a stalwart supporter of poetry in the city.

“Poetry plays an important role in our society by revealing to us our community humanity,” Nenshi says.

Calgary has one of the strongest poetry communities in North America, according to beaulieu. When he travels internationally, people will ask him about Calgary poets by name. It’s a vibrant population that is continuously breaking down barriers and provoking the norm.

“Calgary’s literary reputation is sterling outside of the city, and we have the reputation as being one of the absolute hotbeds of risk-taking poetry on the planet. You want to know where the cutting edge of poetry is in North America? It’s in Calgary,” says beaulieu.

Hyttenrauch notes three reasons for the vibrancy of poetry right now.

“First is that we have a concentration of exceptional poets in the city. Second is that we have a solid infrastructure for public performance and publication, with independent book stores like Pages, Shelf Life and Owl’s Nest, various writers in residency programs and the Banff Centre. Third, there is a real community, with faculty like Micheline, Richard, derek and Beth Everest developing student potential and introducing them to a supportive wider creative community of writers whose debates, readings, classes and writers’ groups support a creative culture,” he says.

“I think the poetry scene in Calgary is pretty cool. It’s actually surprising how many people are at readings and are willing to go up on the stage and share their work,” says Merencilla.

Poetry — and poets — continue to combat being boxed in by those wanting to use them for something other than their original purpose. Turns out, writing poetry is actually a normal, healthy, human thing to do. And Calgary is one of the best places to do it.

It’s the year of the poet at Mount Royal

The Department of English, Languages, and Cultures’ 2017 Writer in Residence is the renowned Di Brandt, PhD and professor emerita at Brandon University. She has published eight collections of poetry and is known as a contemporary writer whose feminist, activist works contrast sharply with her strict, patriarchal and conservative Mennonite upbringing.

2017 Writer in Residence

Slated to be at Mount Royal from March 6 to 10, Brandt will be available to students to discuss their writing, to visit lectures and to give presentations. The pinnacle of Brandt’s visit will be a public reading and lecture.

In anticipation of Brandt’s arrival, we asked her a few questions.

What does it take to be a poet?

All it takes to be a poet is an interest in language, and rhythm, and cadence, and a sense of curiosity, and adventure, and fun and the desire to explore these things further.

Everyone has at least some of that. So everyone is a poet, at least a little bit.

Poetry has taken a hit in the postmodern era, and is no longer considered the “queen of the discourses” — no longer revered and honoured the way it was in the past. And yet, it is still the most powerful way to be in language, and can move people immensely, in the writing, reading and hearing of it.

Why is poetry important?

There’s something deeply transformational and visionary in poetry.

It has an extraordinary capacity to enlarge our sensibility, expressiveness and understanding of ourselves and the world around us. It’s a language of connection, and interconnection — a language that is able to address us in multi-dimensional ways, a holistic language that touches people’s hearts in unexpected, powerful, lovely and tender ways.

It’s a very efficient and simple language that any child can understand and yet that can hold the deepest meanings. It’s a language of inspiration, and hope, and love. Poetry can be silly, deep, philosophical and fun — all at once!

What do you think about poetry in Calgary?

Calgary has become such a hotbed for innovative poetry in recent years. Mayor Nenshi probably had something to do with that, as well as the fine creative writing programs at the universities, and the lively arts scene at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. And the vibrant youthful energies of this growing city. And the electric vibes of the mountains meeting the prairies. A magical place.

Read more Summit

The Path to Indigenization

Reconciling with the past while chartering a course for the future. This is just the beginning.

READ MORE