Changing skies

Fall 2015 issue

No. 3 Service Flying Training School

How Calgary got its wings

The flying school on Mount Royal soil was one of 17 established in Alberta under the auspices of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP).

Over a five-year span, more than 131,000 recruits came through the BCATP, making it one of Canada’s greatest contributions to the Allied victory. Most trainees went on to serve as pilots, navigators, bombardiers, wireless operators and air gunners.

Southern Alberta was a major domain for BCATP bases because of the highly-conducive air training terrain. At that time, the province was sparsely populated, lightly forested and remote from the threat of enemy attack.

Air Commodore A.T.N. Cowley presided over the grand opening of what was known as the Currie Barracks Airport in Calgary on Oct. 28, 1940, according to an account from the Globe and Mail.

More than 1,000 Calgarians attended a grand opening ceremony where they watched a contingent of Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders march in a ceremonial parade past the saluting crowd. Onlookers also witnessed a pair of Harvard aircrafts and five Avro-Ansons circle the sky.

“Visitors were treated to an exhibition of formation flying and acrobatics,” the Globe published in a brief report.

When it opened, The No. 3 Service Flying Training School was one of the largest in the country. It housed six facilities, including a wireless school, two service-flying training schools, repair and equipment depots, and one of the four national training command headquarters.

Like most of the Canadian military airports of its era, the Calgary airfield had three runaways carved in a triangular shape on a prairie plot. With an average length of 940 metres, the airstrips were slightly more forgiving than what was reported to be the national norm. It was a dizzying hub of activity.

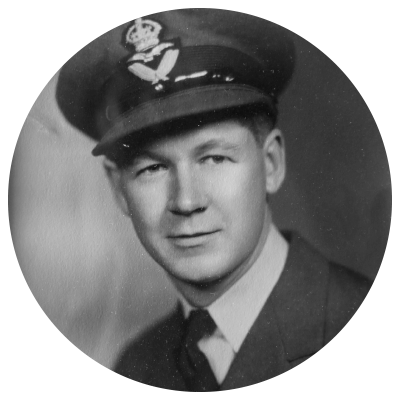

That was the experience of the 21-year-old Robson, who arrived at the No.3 flying school on June 1, 1943 after logging roughly 80 hours of air time.

“It was so busy at times,” says Robson, who later volunteered for Britain’s Bomber Command. “There would be several aircraft ahead of you, all coming in to land. You had to watch out.”

Historical accounts suggest the flying school operated much like a typical campus.

Classes began in the morning and the day typically included four to five hours of flying. Lesson plans were focused on cross-country navigation and engine failure procedures.

Back on the ground, the aerodrome operated as a self-contained community. Three years after opening, the airbase was a maze of sidewalks, flowerbeds and painted corner posts on the thoroughfares.

Baseball, swimming and photography were popular activities. In fact, a basketball team from the flying school was crowned Calgary Foothills League champion in 1944.

The cost of training for combat

Despite the humdrum of curricular activities, learning to fly was a notoriously dangerous pursuit.

A total of 856 trainees were killed while taking part in BCATP— most were Canadians.

A commemorative plaque hangs in the Bissett School of Business in silent recognition of those who worked, trained and instructed at the No.3 flying school — especially the sacrifice of the eight men who died locally during training.

Despite the grim toll, some still credit the Commonwealth plan for reducing the number of injuries. By 1944, only one fatal accident was recorded for each 22,388 hours of flying time, according to The Military Museums of Calgary.

For those who have lost loved ones to armed conflict, there’s no silver lining to war. However, the Second World War was widely considered a financial boon to the Canadian economy. In 1940 the air-training plan cost $2 billion, of which Canada paid 70 per cent. With inflation, that price tag today would exceed $32 billion.

In his book, Saints, Sinners, and Soldiers, historian Jeff Keshen noted the training program had a particularly profound economic impact on the prairies. Keshen, PhD, dean of the Faculty of Arts at Mount Royal, says the impact the air bases had on the community is one of many “fascinating projects for students to explore.”

“The program catapulted Canada’s aerial capacity, including the addition of new airports and ability to support post-war civilian aviation,” says Keshen.

True to Keshen’s point, the value of the BCATP endured long after the No.3 flying school and the base disbanded in September 1945.

Parts of the Currie Barracks airfield remained open until 1964, in part to ensure an emergency runway was available for any pilot using wartime maps. From then until 1983, the abandoned north-south runway was repurposed as a racing strip for sports cars and motorcycles.

Aviation program takes flight

Shortly before Mount Royal moved to its current home in 1972, members of Calgary’s aviation community successfully lobbied the institution’s leaders to start an aviation-training program to address the shortage of commercial pilots.

Housed under the Department of Math and Physics, the faculty was a collection of air force vets. And, given the instructors’ background, the program was based on the training methods used at Royal Canadian Air Force flying schools.

The pioneering class of Mount Royal’s Aviation Diploma program enrolled in 1970, with the ground school moving to the Lincoln Park campus three years later.

“Though students could take courses for normal tuition costs, they had to bear the cost for operating the planes,” former Mount Royal President Donald N. Baker wrote in his centennial-era book, titled Catch the Gleam (published in 2011).

Since then, more than 1,000 airmen and airwomen have earned their commercial pilot wings through the program. Classes are still taught at the University’s main campus, as well as at the Springbank Airport.

The aviation program continues to elevate to new heights, including recent recognition from one of the world’s leading aviation agencies. The Aviation Accreditation Board International (AABI) granted the University accreditation, starting in March 2015.

Although Mount Royal’s modern day aviators are no longer training to fight in the war, many still share an affinity for the armed forces.

Lauren Taylor, who just finished her second-year of the aviation program, is a second-generation flyer with her eyes set on a career as a fighter jet pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Taylor compared her experience to the pilots of the past such as Andy Robson, saying she finds commonalities in their aspirations, pride and passion.

“I feel inspired by attending school here,” she says. “Hopefully Mount Royal continues to be known for its achievements in the aviation field and that legacy only grows stronger from here.”

Past gives rise to new neighbourhoods

Take a tour around Mount Royal University and you will notice that the neighbouring communities — Currie Barracks, Garrison Green and Garrison Woods — reflect the heritage of the land.

Since purchasing the property in 1995, Canada Land Corporation (CLC) has prioritized preservation of historical buildings and public spaces, while building some of Calgary’s most distinct communities.

Valour Park in the Currie Barracks is one of many memorial spots located within a short distance of the Mount Royal campus. There, a trio of bronze statues represents the three branches of the Canadian Armed Forces. Adjacent, Victoria Cross Park pays respect to the 16 Canadian recipients of the prestigious Victoria Cross during the Second World War. In nearby Garrison Green, Peacekeeper Park displays a bronze statue and a Wall of Honour in recognition of the country’s peacekeeping missions.

Custom-designed street signs in the area provide a more subtle nod to the past.

Calgarians may also recognize several commercial buildings with significant ties to the area’s military past. Examples include the Wild Rose Brewery that occupies an old Quonset hut (AF23), and the RCAF Hangar No. 6, which housed a popular farmers’ market for more than a decade. As well, CLC has been working with the Government of Alberta to obtain provincial heritage protection for several landmarks on the 80-hectare Currie Barrack site.

“Commemorating the history of this land is one of our core values,” says Chris Elkey, senior director of real estate with CLC.

By the time construction wraps up, Currie Barracks alone is expected to draw more than 10,000 residents to the area. Elkey describes the current state of the community as a young, family-oriented neighbourhood, with more options for seniors coming on board.

“We’re building a new, high-quality urban neighbourhood,” he says.