The chemistry between us

New major for Mount Royal

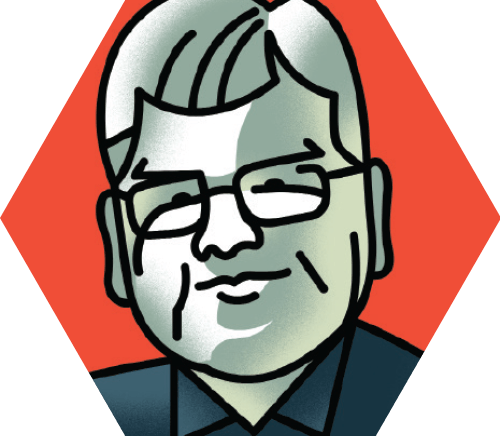

Joe Schwarcz, PhD, who is known for demystifying chemistry on The Dr. Joe Show, which airs on Montreal’s CJAD, has received numerous awards for teaching chemistry and has also appeared hundreds of times on the Discovery Channel, CTV, CBC, TVOntario and Global Television. He was on campus in September to help officially launch Mount Royal’s new Bachelor of Science — Chemistry. Counting as the institution’s 33rd major, a full initial cohort of students is already registered and taking courses.

“Everything in the world works based on a chemical reaction, no matter what you look at. Chemistry is the key. It is the cement that ties all of the other sciences together,” Schwarcz says.

“If you have a feel for what molecules are, what they can do and the reactions they can engage in, you have a pretty good feel for what can and cannot happen in the world. And you also have a pretty good explanation for the ways things work.”

The building blocks towards a future in science

Mount Royal’s chemistry degree sets up graduating students to play a key role in solving global challenges from a variety of career paths. Graduates may end up discovering new medicines, protecting the environment, inventing new products and materials, solving crimes using forensic analysis, inspiring others through teaching chemistry or continuing with studies in graduate school.

While myriad labs are filled with students wearing safety goggles and white coats doing experiments around the world, what differentiates Mount Royal’s degree is Community Service Learning (CSL). CSL means applying education to complex, real-world issues through partnerships in the community. Students who take three CSL courses receive a CSL designation on their MRU transcripts, and all students graduating with the chemistry major will satisfy this requirement.

The Department of Chemistry and Physics has initiated a CSL pilot project with a group of a landowners near Oyen in eastern Alberta testing phosphatase levels in soil. Phosphatase is an enzyme that breaks down the phosphorous that comes with fertilization, so they are studying how much fertilizer residue is in the soil.

“Because we’re small and nimble, we can work with these community groups to carry out these sorts of projects effectively,” says Professor Chris Lovallo, PhD and chair of the Department.

Chemistry components

The Canadian Society for Chemistry breaks up the study into five major branches: organic, inorganic, physical, analytical and biochemistry. Mount Royal chemistry students are immersed in all of these, plus they look into computational and “green” chemistry.

- Organic chemistry is the study of the structure, properties, composition, reactions and preparation of carbon-containing compounds. Because carbon atoms bond easily into molecules, over 95 per cent of all compounds are organic.

- Inorganic chemistry is concerned with the properties and behaviour of inorganic (not carbon-based) compounds, which include metals, minerals and organometallic compounds.

- Physical chemistry is the study of how matter behaves on a molecular and atomic level and how chemical reactions occur.

- Analytical chemistry is the art and science of determining what matter is and how much exists.

- Biochemistry is the study of the structure, composition and chemical reactions of substances in living systems.

- Computational chemistry is where computers are used to solve chemical problems.

- ”Green” chemistry is also called sustainable chemistry and concentrates on designing products that use and produce less hazardous waste.

Second-year student Jaymar Tallo switched to the chemistry major as soon as he saw it was open for registration.

“I went straight to the science advisors and asked them to put me into the major,” Tallo says. “I liked the chemistry labs in high school and the theory of chemistry. I also think that my high school chemistry teacher influenced my decision. Thanks to Ms. Lovallo for inspiring me.”

Coincidentally, Tallo’s high-school teacher is the spouse of Mount Royal’s chair of the chemistry and physics department. He hopes to use his education for graduate studies in chemistry or pharmacology, and says that he appreciates how much MRU professors invest in seeing students succeed.

“The teachers do not see the students as numbers, but as people,” Tallo says.

Chemistry professor Nathan Ackroyd, PhD, says Mount Royal stands out through its commitment to personalized learning. “I’ve had students contact me four years after taking just one class to say, ‘I don’t know if you remember me, but I was in your class and I need a letter of recommendation.’

“The truth is, I do remember them. If you want to know who your instructors are and you want them to know you, this is your best option. And that’s an opportunity you don’t get very many places,” he says.

The chemistry major will, like other Mount Royal degrees, embody this principle. And even though the degree is still in its infancy, MRU graduates have been making their mark in the field.

Professor Brett McCollum, PhD says, “We’ve been doing a really excellent job at Mount Royal of drawing students in to do research. Students have been going on to post-graduate studies based on their research in chemistry, even though MRU previously didn’t have a major in chemistry.”

Bachelor of Science — Health Science (2017) alumnus Brandon Shokoples performed undergraduate research with professors McCollum and Carol Armstrong, PhD, while at MRU. He subsequently presented his research on chemistry language development at the Canadian Chemistry Conference and Exhibition in Toronto and the American Chemical Society Conference in San Francisco. He has co-authored two papers on the subject (one published and one under review) and is currently at McGill University as a graduate student in experimental medicine.

In addition, McCollum and fourth-year student Darlene Skagen, who is majoring in cellular and molecular biology, are teaming up with the University of Illinois Springfield to develop students’ professional identities, communication confidence in chemistry, content mastery and appreciation for chemistry as an international language.

Research assistant Jordan Hofmeister (Bachelor of Science — General Science (2018)) won second place in the Graduate/Undergraduate Student Oral Competition category at the 101st Canadian Chemistry Conference and Exhibition. His work evaluates the experience of peer leaders (similar to teaching assistants) in a flipped classroom environment, (where students work through challenging problems in class with the support of the professor and peer leaders, and complete preparatory learning with their textbook for homework).

McCollum sees a bright future for students. “We’re very excited for this opportunity now to move students through the new chemistry program, knowing that we’re going to produce some of the best graduates any university has to offer.”

The possibilities open to students with a degree in chemistry are unlimited. Mount Royal is already creating leaders in the field and has the ability to make an atomic impact on the world of science.

— With files from Peter Glenn

Science is an attempt to understand how we all came to be and continue to exist on the planet. Here, five Mount Royal chemistry professors describe life in terms of chemistry.

Professor Nathan Ackroyd, PhD

Ackroyd is co-author of Organic Chemistry: Mechanistic Patterns (1st Edition), which has been adopted by 20 universities across Canada, including Mount Royal.

“When you think of life, you’re thinking of thoughts, which is very meta. But all of the processes that go on, that make your heart beat, that cause signals to happen and then travel down nerves, to feel a surface, all of those things involve chemical processes.

“Life is really a very, very complicated chemical reaction.”

Professor John Chik, PhD

Chik received his PhD from Princeton University in the field of protein crystallography/ chemistry.

“There was a time in the history of chemistry when it was thought to be a discipline separate, or alongside, life. If you look at table salt and an ant, they’re very different things. But the laws that govern them both are the same.

“From the lens of biochemistry, life is about how biology is able to reorganize atoms. All of the energy that we have, that we use industrially and biologically, is essentially a rearrangement process. You’re not creating new atoms. You are rearranging them to create energy. And energy is life.”

Professor Brett McCollum, PhD

McCollum is a Nexen Scholar of Teaching and Learning and recipient of a Mount Royal Faculty Association Teaching Award (2016) and a Mount Royal Distinguished Faculty Award (2017).

“Mathematics allows us to symbolically represent interactions. Those interactions can be described based on the principles of physics. We apply mathematics and physics in chemistry to describe chemical reactions. And it’s those reactions that drive and facilitate life.”

Professor Susan Morante

Morante has been with Mount Royal for more than 30 years. She has worked in various research and industrial labs, contributing to an understanding that a premature infant needs a different type of milk formula than a full-term infant.

“I actually think of life in terms of science, generally. I look at everything with that questioning that I think is the hallmark of a scientist. ‘What’s going on? Why did this happen? What can I find out about it?’

“One of the biggest things that we do in science is remind students that it’s OK to ask questions. That should be what we’re really doing, is asking questions about the universe and about the world.”

Professor Jonathan Withey, DPhil

Withey earned his doctorate in chemistry at the University of Oxford.

“For me, chemistry helps us understand life. It helps us measure the environment around us. It’s an enabler of our own collective futures. We can monitor and detect things around us, but then we can also develop ways to influence those things in a positive manner. How can we influence things in a way that allows us to thrive?”

The incredible periodic table of elements

The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2019 as the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements, 150 years after Mendeleev’s first publication. Mount Royal chemistry students are taking part in an international collaborative project spearheaded by the University of Waterloo, where they are focusing on the impact of one specific element to go into a timeline organized by year of discovery.

Modern chemistry’s roots are in alchemy, which was first recorded about 4,000 years ago. It was the idea that one element could be transformed into another, which is now possible using controlled nuclear reactions. Alchemists were mainly trying to turn base metals — lead, in particular, into gold — for the obvious purpose of creating wealth.

They weren’t successful, but what they did end up doing was producing a number of different alloys, which in turn led to the discovery of a number of different elements. This was the beginning of the periodic table of elements, a remarkable visual one-stop shop for all 118 elements discovered so far. Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist, first published a rudimentary table in 1869, knowing it was incomplete but that it would be filled in by future scientists. The table is organized by atomic number (the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom), as well as chemical behaviours. Metals are to the left, non-metals are to the right and non-reactive, or noble gases, form the farthest right column.

Its importance to the world of science can’t be overstated. By looking at the periodic table of elements reactions can be predicted without the need for a lab. It is essentially the key to all things chemistry, and provides the inspiration for innovation in the field.

Chemistry is natural, not naughty

Although it forms the basis for the understanding of science as a whole, the word “chemistry” can conjure up images of chemists as sorcerers summoning black magic or scientists playing fast and loose with stable states.

In his article, “Why do people hate the word ‘chemicals’?” Professor Mark Lorch, PhD, of the University of Hull in the U.K., describes the phenomenon as “chemophobia,” and says it results in a “bad rap” for the field. Biology implies plants, animals and nature. Physics conjures up images of space, laser beams and the wonders of the universe. Chemistry, though, has become synonymous with poisons, toxins and weapons.

“Chemicals are looked on as dangerous things,” says Joe Schwarcz, PhD of the Dr. Joe Show. “This is an absurd view because chemicals are just things. They are the building blocks of everything, of all matter. They are not good, they are not bad, they are just things.”

In fact, today’s “pharmacy” was once called the “chemist’s,” which had shelves lined with minerals, herbs and animal matter, all thought to have healing properties. But pharmacology evolved and compounds are now synthesized through sophisticated chemical processes, resulting in stronger, more effective medications and treatments.

“One of the biggest myths out there is that if something is natural it’s better. That it’s better or safer than something made in the lab, which of course is not the case,” Schwarcz says.

What “scares” people are the names of chemicals, says Professor Chris Lovallo, PhD and chair of Mount Royal’s Department of Chemistry and Physics. An example is nitrates, which are known to cause cancer. “If you buy normal bacon, the ingredient list will say sodium nitrate. If you buy the ‘no-chemical’ bacon, it will say celery salt, but celery salt actually contains nitrates as well.

“’No-chemical’ bacon actually has more nitrates and more sodium than standard bacon. But they can say there are no chemicals in it because they get it from a ‘natural’ source.”

There are also estimates that the average woman puts approximately 168 chemicals on her body every day (shampoo, conditioners, makeup, skin care cream, etc.). Many women check the chemical make up of each individual product, but the real danger may be in all those chemicals being applied at one time.

Schwarcz advocates for balance and reflection within all sciences.

“While there are no such things as safe or dangerous chemicals, there are safe ways and dangerous ways to use them. What has to be considered, always, is that there is a risk/benefit ratio. Chemicals are not good or bad, it depends on how you use them.”

WHAT IS “CHEMOPHOBIA?”

James Kennedy, a chemistry teacher at Haileybury Institute, one of Australia’s largest and leading independent schools, created this list of the actual chemical elements of coffee beans as an attempt to combat what is known as “chemophobia.” He has done the same for other foods such as eggs, bananas, blueberries, kiwis, lemons and so on, all of which contain what he calls “scary-looking ingredients,” that are, in fact, completely natural.

“Natural isn’t always good for you and man-made chemicals are not inherently dangerous,” Kennedy says.

THE NATURAL COFFEE BEAN

Ingredients: Caffeine, Chlorogenic Acids (5-Caffeoylquinic Acid, 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic Acid, 3-Caffeo-4-Feruloylquinic Acid, 5-P-Coumaroylquinic Acid), Cafestol, Kahweol, Amino Acids, Soluble Dietary Fibre (Galactomannans and Type II Arabinogalactans), Galactose, Arabinose, Furans, Pyridines, Pyrazines, Pyrrols, Aldehydes, Melanoidins, Fatty Acids (Linoleic Acid, Oleic Acid, Linolenic Acid, Coffeadiol, Arabiol I), Ash, Sterols (4-Desmethylsterols, 4-Methylsterols, 4,4-Dimethyl-Sterols, Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-Tocopherols), Flavourss (2,3-Butane-Dione, 2,3-Pentanedione, 1-Octen-3-One, 2-Hydroxy-3-Methyl-2-Cyclo-Pentene-1-One-Propanal, 2-Methyl-Propanal, 3-Methyl-Propanal, 2-Methylbutanal, 4-Methylbutanal, Hexanal, (E)-2-Nonenal, Methional, Methanthiol, 4-Methyl-2-Buteno-1-Thiol, 2-Methyl-4-Furanthiol, 5-Dimethyl-Trisulfide, 2-Furfurylthiol, 2-Furan-Methanethiol, 2-(Methyl-Thiol)-Propanal, 2(Methylthio-Methyl) Furan, 3,5-Dihydro-4(2H)-Thiophenone, 2-Acetyl-2-Tyazoline, 4-Methylbutanoic Acid, Damascene, 4-Hydroxy-2,5-Dimethyl-4(2H)-Furanone (Furaneol), 2-Ethyl-Furaneol, 4-Hydroxy-4,5-Dimethyl-2(5H)-Furanone (Sotolon), 5-Ethyl-4-Hydroxy-4-Methyl-2-(5H)-Furan-One (Abexona), 2-Ethyl-4-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-(5H)-Furanone, 2-Methoxy-Phenol, 4-Methoxy-Phenol, 4-Ethyl-2-Meth-Oxy-Phenol, 4-Vinyl-2-Methoxy-Phenol, 4-Ethenyl-2-Methoxyphenol, 3-Methyl-Indole, Vanilline, 2,3-Dimethyl-Pyrazine, 2,5-Dimethyl-Pyrazine, 2-Ethyl-Pyrazine, 2-Ethyl-6-Methylpyrazine, 2,3-Diethyl-5-Methylpyrazine, 2-Ethyl-3,5-Dimethylpyrazine, 3-Ethyl-2,5-Dimethylpyrazine, 3-Isopropyl-2-Meth-Oxypyrazine, 3-Isobutyl-2-Methoxy-Pyrazine, 2-Ethenyl-3,5-Dimethylpyrazine, 2-Ethenyl-3-Ethyl-5-Methyl-Pyrazine, 6,7-Dihydro-5H-Cyclopentapyrazine, 6,7-Di-Hydro-5-Methyl-5H-Cyclopentapyrazine, 3-Mer-Capto-3-Methylbutyl Formate, 3-Mercapto-3-Methylbutanol), Minerals (Potassium, Phosphorus, Sodium, Magnesium, Calcium, Sulfur, Zinc, Strontium, Silicon, Manganese, Iron, Copper, Barium, Boron, Aluminum)

Source: jameskennedymonash.wordpress.com

Read more Summit

Cybersecurity warriors: frontline of defence

Cybercriminals are hitting large institutions hard, relying on base human emotions and frailties for their illicit gains.

READ MORE