Coming together at the end

A palliative care program for people who are experiencing homelessness is helping them die with dignity.

Coming together at the end

In the award-winning 2015 Calgary Herald photo-documentary series, Barbi Harris describes herself as “a tough bitch.” Fiercely independent, Harris — 54 years old and homeless — had multiple health issues and spent her last days telling her story to and having her picture taken by photojournalist Leah Hennel.

Widowed at 35, Harris experienced traumatic life events that resulted in her living on city streets, struggling with addiction, diabetes and COPD and, finally, receiving a cancer diagnosis.

Find a way to do better for people like me, was Harris’s final ask of Dr. Simon Colgan, the physician who, in his own words, had the privilege of treating her during her final admission to hospital. That dying wish would come to inspire Colgan to create the Calgary Allied Mobile Palliative Program (CAMPP).

“People often want to die how they lived, and we shouldn’t expect any different for someone living in homelessness,” says Rachael Edwards, a Mount Royal Bachelor of Nursing (2010) alumna working as a street nurse with CUPS (Calgary Urban Project Society) and Colgan’s CAMPP co-founder. “They are incredibly resilient and independent folks, and the last thing we should be doing is trying to take that away at their end of life.”

Colgan told a room full of nurses that Harris was “a real force of nature” at a spring palliative care conference in Calgary. “I felt a real sense of frustration from her that she was losing her independence. She wanted to be on the street, but could no longer be on the street. She cared deeply for the community of people she loved. The CAMPP program is Barbi’s legacy, and I’d like to think we’re honouring her wishes.”

According to Calgary’s point-in-time count in the spring of 2018, Harris’s community totalled 2,911 individuals. A special tabulation by Statistics Canada for Calgary based on 2016 census numbers also states that 17,000 city households are at risk of homelessness because of earnings of less than $30,000 per year and spend more than half their income on rent. At the very least, the numbers total a small town’s population living inside the city. With an average life expectancy of just 54 years, Harris’s death fell directly in line with the statistics, highlighting the disparity in health between those without permanent or stable housing and the rest of the population, whose average lifespan is now 83 years.

Unfortunately, many, if not most, of her community die begrudgingly in acute care facilities without a voice and without the dignity and respect owed to them by society. For those experiencing homelessness, hospitals are often seen as places people go to but do not return from. In fact, some die without their true identity having even been known.

A system without judgment

The non-profit agency CUPS has a full-service primary care clinic to simplify the health-care process for clients. In addition to general health care and laboratory services, there are dental, blood and pre- and post-natal care clinics. Mental health specialists are available, along with child and family development centres and parent education programs.

CAMPP is funded until October 2019, but Edwards says the need is ceaseless. Her dream is a dedicated hospice with full-time staff for CAMPP clients, who, while difficult to house, have tremendous survival abilities.

For this group, Edwards and Colgan find it’s best to work through the lens of harm reduction — reducing the risks associated with substance use and its associated behaviours rather than insisting on abstinence, which is unrealistic (and paternalistic).

The biggest challenge for CAMPP is tracking clients down. Typically, Edwards receives referrals from her contacts at the shelters and in the community, and from there it’s up to the clients to choose to let her in to their lives. Having worked with people experiencing homelessness in Calgary since 2006, she is known as someone who can be trusted — in the way that only someone who finds a prosthetic leg in the snow downtown and knows who to return it to can be trusted.

Some of the first questions she asks are, “What kind of food do you like and what do you take in your coffee?” When people have a terminal diagnosis, that’s what matters, and that’s Edwards’ way in.

Edwards firmly believes in the right for each individual to die with an equal level of care and comfort, driving her to be the voice for those who often don’t have anyone else. It’s regularly assumed that there must be friends and family available for emotional and other support, but for Edwards’ clients, she and her colleagues are usually all they have.

“People die in the shelter all the time and nobody knows about it. Or, people die lonely in the hospital with nobody with them. This way, they have someone.”

Edwards feels wholeheartedly that the final leg of the journey of life is one nobody should have to walk alone. But in her line of work, goodbyes are inevitable.

“There’s definitely ritual that goes into each loss,” Edwards says. “For me it’s about acknowledging the loss in my own life, and also the positives that came from my experience with that person, and then remembering all of their funny and amazing stories of resilience and perseverance … their incredible senses of humour, their jokes, their stories, their values. I’m privileged to have had the chance to share that with them.”

Edwards recalls visiting her first client in his home when she was a brand-new nurse. She went with a colleague, who had built a rapport with the man through previous visits. When she entered the client growled at her, grabbed his crack pipe and lit it.

“Beyond being vulnerably housed or homeless, our clients are also socially complicated, medically complex, and when you also factor in addictions and a terminal diagnosis, it can be challenging — but pleasantly so. If you only knew the stories behind the complexities, though, behind the people — it would break your heart every day. People need to realize that nobody would choose to have that life. Nobody.”

A system without judgment

Jerome

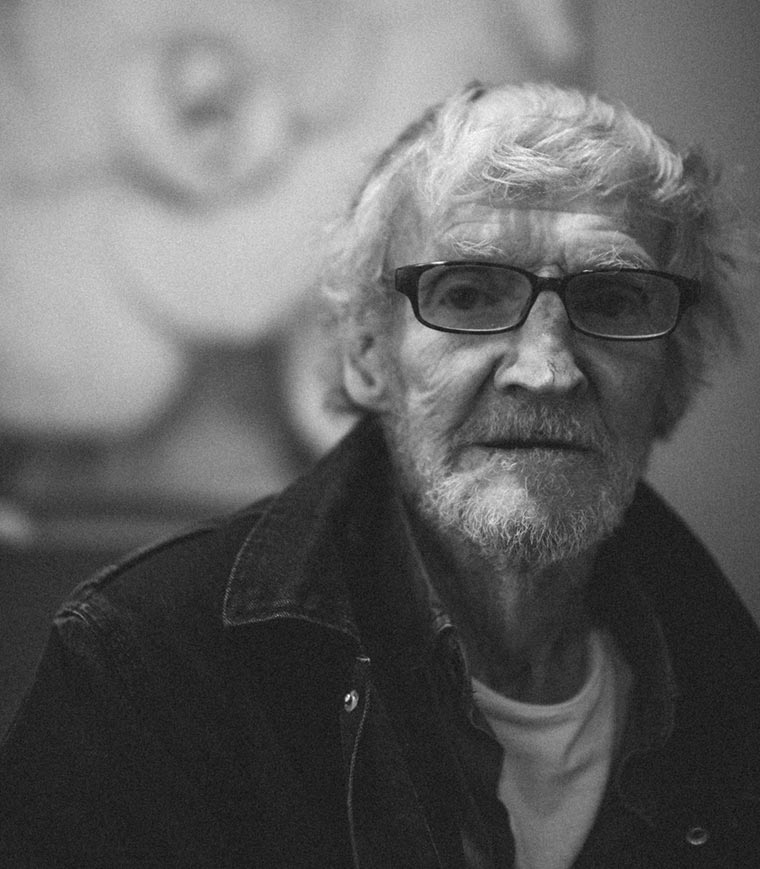

Jerome

The challenge of staying on top of medical treatments for clients who do not have a phone, mailbox or Internet access, and where missing one appointment has a cascading effect, is often insurmountable. As well, CAMPP clients are not used to compassion and often resist the idea of being cared for.

In his 70s, Jerome Domanski describes himself as a true “hobo,” having travelled around North America for much of his life doing odd jobs. With a heart operating at only 15 per cent capacity, he is at serious risk for heart attack, stroke and organ failure. Domanski was referred to CAMPP through Calgary’s Alpha House, and Edwards says it took two months of building his trust before he agreed to move into a transitional suite.

At his regular appointment with Edwards, Domanski described difficulties with his medication, which he has a history of not taking. He admitted that two years ago in Montreal, where he was first diagnosed, he would throw out his pills because they made him sick. Edwards worked with him to change his drug schedule to ease the side-effects and reminded him of an upcoming doctor appointment to deal with a severe pain in his leg.

Domanski, impatient, said it would just be easier for him to go on the street to buy some morphine. Edwards disagreed, saying he would likely get fentanyl, which could kill him.

“I’m dying anyway,” was the response.

Using the harm reduction mantra, Edwards quickly put in a call to Domanski’s doctor, who happened to be on vacation but answered the call anyway. She described what was happening and asked if Domanski could get a morphine prescription right away. The doctor agreed and Domanski received his medication that day.

What could have been an extremely perilous situation was de-escalated in minutes. When asked about Edwards and what she does, Domanski said, “She does a good job. (Without her) I’d be dead.”

Balancing between the cracks of society

Helping those at risk of or experiencing homelessness inspired Edwards even before hearing about Barbi Harris.

Edwards’ path as a street nurse veered towards CAMPP’s conception when she met Brad through a shelter agency after he had complained about abdominal pain, which was eventually found to be a cancerous blockage. After a fall, Brad’s condition deteriorated and his doctor recommended a hospice, where he spent his final three months. Brad had a warm bed, nutritious meals and money left in his pocket at the end of the month to take Edwards out for coffee. He reconnected with family, including his 13-year-old child.

Edwards recalls being at Brad’s side for his final heartbeat. “It was a privilege,” Edwards recounts. “It was really pretty amazing.”

While she was having a cry outside the hospice with colleagues from the DOAP Team (Downtown Outreach Addictions Partnership), a well-dressed man in a cowboy hat whom Edwards recognized from the shelter began walking towards them.

“He was a blood relative, as well as a friend,” Edwards says. “We had to tell him he had missed Brad by less than 30 minutes. He just solemnly and silently turned and walked away.”

Edwards later learned that the man had spent the previous two weeks detoxing and staying with his sister in order to clean up so he could go to the hospice sober enough to say goodbye.

“I realized that although we had done right by the patient, we still had not done right by the community,” Edwards says.

Missing a final resting place

Missing a final resting place

Although many shelters and agencies have built their own mourning rituals, Edwards hopes one day a public memorial will be established in Calgary as a place for people to say goodbye and honour those who have died.

“My clients understand loss more than anyone,” Edwards says. “And I swear they feel more than the average people. They seem to be more in tune, and intuitively know when people are feeling vulnerable and are there for each other. I’m constantly amazed by the care, love and strength in that group.”

Edwards says that some sort of local memorial in Calgary would help those experiencing loss to externalize their grief, rather than internalizing it, which can lead to further trauma and perpetuate or exacerbate addictions issues.

Some shelters, including the Calgary Alpha House Society, host regular events in remembrance. Cultural ceremonies such as sweats and smudges mark the beginning of a year of mourning for those who’ve had their final heartbeat, and assist in letting go of those who died the previous year.

Mount Royal’s support of CAMPP

Edwards knew as a student in the nursing program that she didn’t want to work in a hospital. CAMPP is definitely her dream job. She has stayed well-connected with MRU to share resources, and in turn the University has helped support development, grant writing and research for CAMPP. The Office of Research, Scholarship and Community Engagement also holds and manages a significant grant from the Calgary Foundation exploring the CAMPP model and building on curriculum for social care workers. The funding is responsible for extending CAMPP for two years beyond its pilot phase.

More grant funding and support from the St. Elizabeth Foundation has matched what’s being done through the Calgary Foundation, with a nation-wide study of palliative care models for people experiencing homelessness being created.

Sonya Jakubec, PhD, is a professor in the School of Nursing and Midwifery and a passionate advocate for CAMPP in MRU programming. She has helped link those doing similar work in Victoria and Toronto.

“Ideally all of our work locally will lead to long-term funding from Alberta Health Services,” says Jakubec. “Our national goal is palliative equity.”

Recognized with an Outstanding Alumni Award — Community Service in 2017, Mount Royal communications alumnus Tim Richter is president and CEO of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness. He knows all too well the need for the work Edwards, Jakubec and their colleagues are taking on.

“Palliative care for people experiencing homelessness has become a sad necessity because the population is aging — in fact seniors are among the fastest growing population,” Richter says. “Many in their late 50s and early 60s become ‘functionally seniors’ due to chronic illness and the ravages of homelessness. For far too many people the cumulative effects of prolonged homelessness lead to premature death.”

Richter explains that the health-care system is notoriously difficult to navigate for anyone and is exponentially more difficult for people experiencing homelessness, who face stigma, hostility or benign neglect. As a result, many avoid it.

“If they are not engaged in the health-care system in a meaningful way and they have no one there to advocate for them, accessing end-of-life care is unlikely,” he says.

Many of Edwards’ clients fear being a burden — to family, friends and even care workers. But CAMPP is changing that, giving clients support, independence, choice, respect and dignity.

“Since connecting with CAMPP, I look forward to more than tomorrow now,” says one.

— With files from Michelle Bodnar

CAMPP

Read more Summit

Aging: Reformed

This three-part series takes a look at how Mount Royal is building educational (and social) partnerships with a seniors residence.

READ MORE