Spring 2016 issue

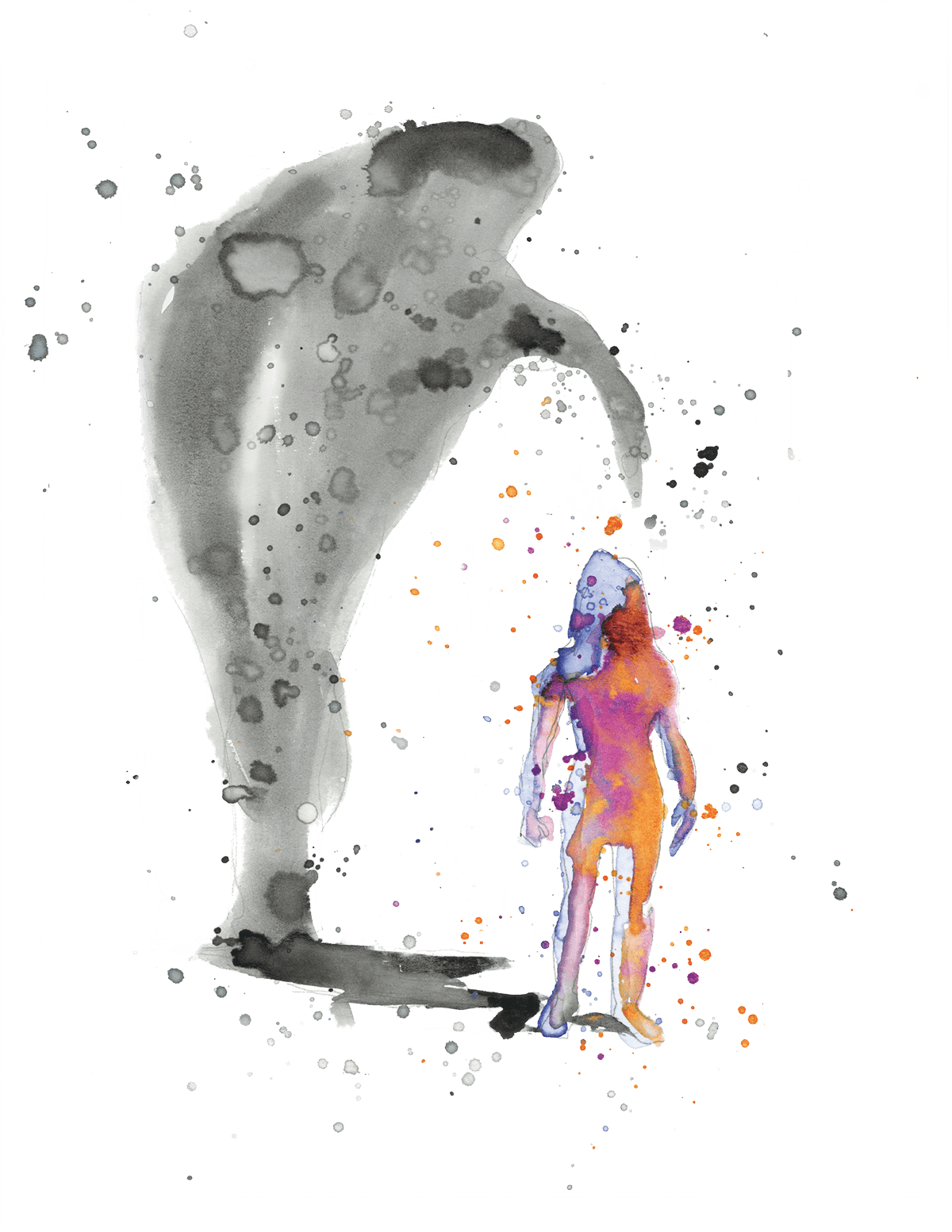

COMING OUT OF THE SHADOWS

Incidents of violence on campus are being reported, and that’s a good thing … Mount Royal professor calls for transparent and stricter survivor-focused protocols when it comes to campus violence in Canada

Mandy Stobo is the visual artist who created the bad portrait project, celebrating our self-worth by making our flaws our beauty and helping make art accessible

Only a generation ago, it would have been unheard of in the post-secondary sector to be encouraged by the number of reported incidents of relationship and sexual violence on a university campus, let alone publicize them.

Well, in a Dylan-esque way, “the times, they are a changin’.”

A 2014 CBC News story shared an exclusive investigation that collected data from 87 universities and major colleges exposing myriad of inconsistencies in reporting and data collection that brought to light the alarmingly low rate of reported incidents of sexual violence on Canadian campuses.

The reality is that the number of students who experience violence, both on- and off-campus, stands as a black eye for post-secondary institutions across the country — recorded or not. The National College Health Assessment (NCHA), an internationally-recognized student survey, which collects precise data about student health, habits, behaviours and perceptions, indicated that approximately one in three Mount Royal students had experienced some kind of violence in one or multiple relationships.

“That’s a staggering number,” says Gaye Warthe, PhD, chair of the Department of Child Studies and Social Work, who has done much research in the area. She adds, however, that Mount Royal needs to know these stats in order to allocate resources accordingly.

In 2008, 2010 and 2013, Warthe and her co-researcher, Leslie Tutty of the University of Calgary, began taking a look at Mount Royal’s dating violence rates. They were concerned to find that about a third of students had experienced some kind of abuse, either before or after enrolling at Mount Royal. However, it’s not all bad — Warthe explains that higher numbers of reported cases point to something, well, positive — schools with what is perceived as high numbers of reported cases underscore the need to provide an environment where students feel safe to come forward and report incidents of violence.

“It means we can address the problem by working towards a cultural change — work towards keeping people safer — because we have a barometer of what we’re dealing with as a university,” she says.

Studies on dating violence in post-secondary began in the early ‘80s. In the U.S., colleges and universities have had mandatory reporting policies for sexual violence since 1972, when Title IX was introduced, a federal law requiring gender equity and protecting students from harassment and bullying based on sex. Since 2013, these same schools have been required to report on dating, domestic, sexual violence and stalking, and hate crimes.

According to Warthe, who is also a registered social worker, it’s time Canada followed suit.

One in three Mount Royal students had experienced some kind of violence in one, or multiple relationships.

— The National College Health Assessment student survey

“Title IX came into effect in the U.S. in the ‘70s, then in 1990 the Clery Act focused on mandatory sexual violence reporting and prevention. In 2013 the act was expanded with reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act and the definition now includes all of the above mentioned,” explains Warthe. “For Canadian campuses to go backwards by reporting only sexual violence, not all relationship violence, seems ludicrous.”

Mounting public pressure over the past few years has marked a major milestone in terms of a broad and long-sought change across the post-secondary sector in Canada, says Warthe. Her work at Mount Royal has had the unwavering focus of ringing in this new era — in the city and across the province.

The CBC report publicly highlighted the lack of policy on sexual violence, but more importantly, the lack of protocols for responding to disclosures of all types of relationship violence (emotional, physical, sexual, stalking) and addressing safety.

“The fact is that it’s happening, and we know it’s happening,” Warthe says. “But, without accurate and reliable data we’re working blindly to create prevention strategies.

“The protocols for handling disclosures are paramount to creating a culture in post-secondary that encourages students to seek help when they need it, and that’s what we’re working to develop and share with other post-secondary institutions.”

Warthe has been involved in developing protocols for screening for domestic violence in over 64 agencies in Calgary, including emergency departments and schools. She also helped develop protocols for the specialized domestic violence court.

Gaye Warthe

Chair, Department of Child Studies and Social Work

When she started working at Mount Royal full time in 2005, she and colleagues Patricia Kostorous, PhD, faculty member in the Bachelor of Child Studies and Cathy Carter-Snell, PhD, faculty member in the School of Nursing and Midwifery, recognized that post-secondary was behind the rest of the community in developing a survivor-centred response to relationship violence.

“As a social worker, I felt an obligation to address that gap,” Warthe says.

Warthe’s work of late coincides with Mount Royal’s Diversity and Human Rights services, and Campus Security’s work toward innovative protocols for responding to disclosures. An imperative step in the right direction is making sure that students have the tools and resources available to feel they can safely come forward. Mount Royal has several groups helping to lead the charge.

Peter Davison, formerly of the Calgary Police Service (CPS) and now Mount Royal’s manager of Security Services, started his career in law enforcement in 1981 before accruing 27 years of experience while climbing the ranks to Deputy Chief of CPS. Yet, of all of his accomplishments on the force, Davison speaks most proudly of his leading role in establishing the CPS’s domestic conflict unit and specialized domestic violence court.

“That model has grown into one of the most successful and complimented programs in North America,” he says.

Davison is looking to bring that experience to the table when talking about procedures for handling disclosures of relationship and sexual violence on campus.

As momentum continues to build around these grassroots initiatives, “We’re using what we learn to help to define our direction and combat the issues as a campus,” says Warthe. “And through this approach, Mount Royal can continue to be a leader in Alberta and contribute our findings to influence larger change in the sector.

“The key to an effective approach is recognition that violence prevention is about community change. We cannot focus only on one type of abuse, such as sexual violence, and ignore other types of violence that occur in dating and domestic relationships. Nor can Mount Royal develop policies for one group of people on campus. We cannot ignore that MRU employees, as well as students, are experiencing violence in relationships and increasing safety in our community means creating protocols for responding to disclosures of abuse and campus policies for students and employees.”

Read more Summit

Semblance of Faith

A campus community defies dinner-party etiquette and dares to talk religion.

READ MORE