It will be hard to forget the visual from the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Captiol in Washington, D.C., when a shirtless, body-painted man wearing a fur hat and horns participated in the storming of the Capitol under the names of “QAnon Shaman,” "Q Shaman" and "Yellowstone Wolf.” Acting as a manifestation of the conspiracy theory that created him, his mythological appearance was emblematic of the fantasy and fables that the QAnon movement has attempted to proselytize into reality, including that former President Donald Trump was involved in an important secret war against elite Satan-worshipping pedophiles in government, business and the media.

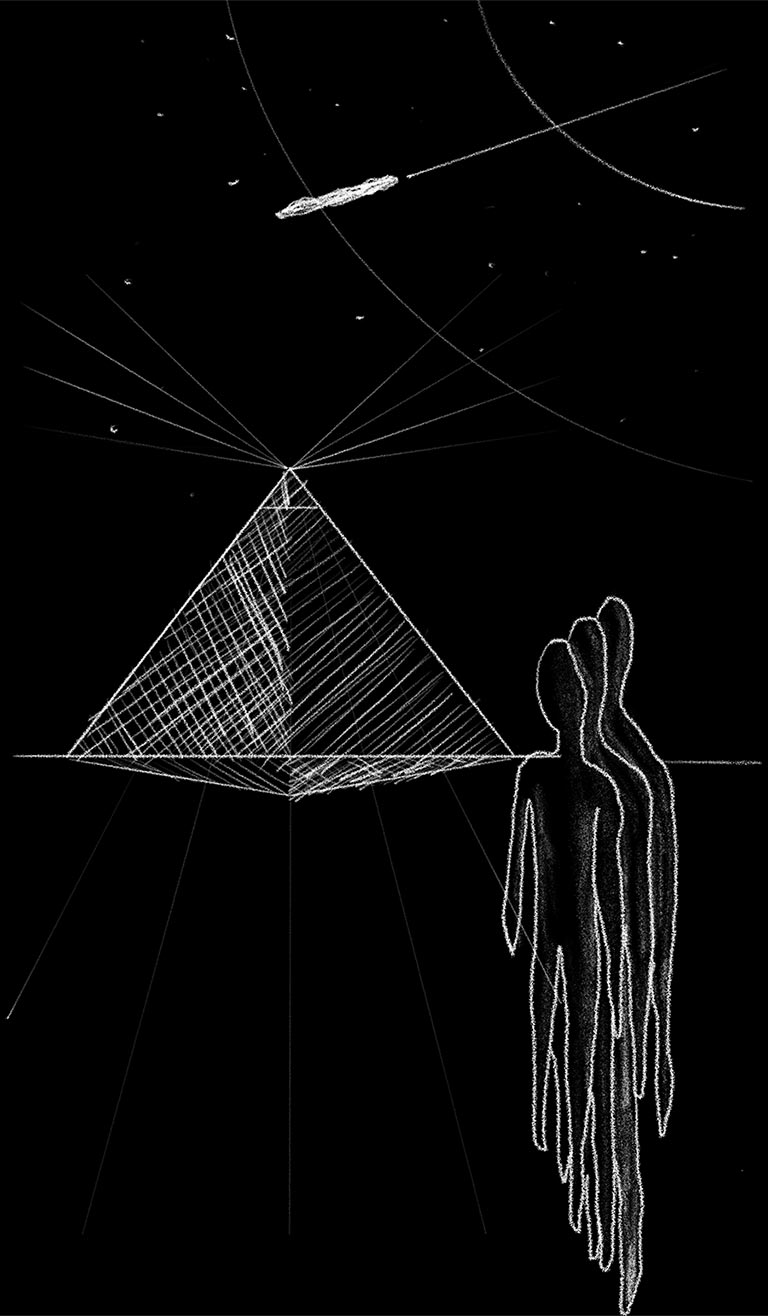

Although the “QAnon Shaman” has since expressed regret for his involvement in the attack, QAnon remains a safe space for conspiracy theories. These conjectures range from the mass harvesting of adrenochrome from the blood of children for the “elites'' to inject into themselves for long life to lizard people in disguise planted in high positions. Each one is based on what the New York Times describes as the “global cabal theory” in the November 2020 article, “ When the World Seems Like One Big Conspiracy.” The global cabal is purportedly secretly running the world, puppeteers controlling everything from behind the scenes. These people are often described as the “illuminati,” shadowy figures with boundless powers who are able to influence all aspects of society. They represent one of the main ingredients of any conspiracy theory that thrives — a demonized “other,” a common enemy. Other factors that contribute to the spread of a conspiracy theory are economic disparity and disenfranchisement, a distrust of mainstream media and, of course, the internet.

The ease with which misinformation can now be shared has conspiracy theories forming a kind of permanent pollution throughout the online world that is often difficult to see through. Brandwatch.com says that as of December 2019, the internet had 4.54 billion users and 3.725 billion active social media users, each with an average of 7.6 different accounts. Links are shared exponentially across those accounts, and there just aren’t enough fact checkers in the world to ensure the legitimacy of everything.

The events of Jan. 6 demonstrate that violence can be a real and dangerous outcome of conspiracy theories. Questioning where these ideas come from and how they proliferate is a step towards understanding the conspiratorial mind and how societal issues and constructs are contributing to less understanding among us.

Those who fall into the conspiracy theory trap usually feel ignored, scorned and even ridiculed by society, says Dr. David Aveline, PhD, associate professor of sociology. Being the owner of “real” information and part of a select group can provide much wanted self-importance. If a person has been raised to question the “establishment’ and has a close social circle that supports their beliefs, they will feel validated.

Those who believe in conspiracy theories also have a tendency towards dogmatism, as evidenced by former President Trump’s hard-core “birther” campaign during the Barack Obama presidency and his continued claims that the 2020 election was “stolen” from him. Dogmatism insists on the validity of a specific claim without consideration of evidence or differing opinions and is a trait that leads to “hardened belief systems,” says Mount Royal Professor Emerita Dr. Judy Johnson, PhD, in her December 2020 article, “ The perils of dogmatic certainty in uncertain times,” published in the Toronto Star. Johnson taught clinical psychology at MRU for 23 years.

In addition to an “otherness,” and an inability to accept differing views, the psychology behind believing something that has not been “proven” is also rooted in personal experience.

Using the biopsychosocial framework normally employed in abnormal psychology, the intersections between biology, psychology and socio-environmental factors can help illuminate why some minds “click” on conspiracy theories more quickly than others, explains psychology instructor Dr. Monica Baehr, PhD. She describes Trump as a “narcissistic” and “antisocial” person who grew up with the “ruthless” modelling effect of his father.

"History indicates that this led to a personal as well as business environment that encouraged Donald to feel entitled to do whatever he wanted, and a seemingly desperate need for success regardless of cost to others. These likely were all contributing factors as to why he is more prone to believing conspiracy theories than others,” Baehr says, adding that Trump could also be prone to a form of anxiety.

"I think the way to fight conspiracy theories is to enfranchise people. To not define them as the dregs of society. If you can give people self-worth, and give them the sense that they're actually participating and contributing to society, then I think that conspiracy theories will lessen."

David Aveline, PhD

Associate professor of sociology

"Personal experience, exposure, is one of the best ways to persuade people. Fear messages are not effective. Keep the dialogue going and provide information, but in a positive way. Persuade people in a way that's moderated and address their actual grievances. Acknowledge that you understand where they're coming from."

Monica Baehr, PhD Psychology instructor

“An undergraduate *general* education can lead to the appreciation of a plurality of methodologies informing human inquiry. That, including an enhanced capacity for quantitative reasoning, scientific understanding and an appreciation of diversity of values, beliefs and identities, is crucial."

Karim Dharamsi, PhD Philosophy professor

People will also surprisingly easily believe two seemingly contradictory things, something psychologists refer to as cognitive dissonance. Taking the Pizzagate conspiracy theory for example, how is it possible to continue to believe that Democrats were running a child sex ring out of the basement of a pizza parlour that, it turned out, doesn’t even have a basement?

Cognitive dissonance is so pervasive that when something is not confirmed, beliefs tend to get even stronger. The theory was developed by social psychologist Leon Festinger, who co-wrote the non-fiction book When Prophecy Fails in 1956 about a group of UFO believers called the Seekers.

“It was about a cult who was convinced that at midnight a flying saucer would come to take them away to another planet,” Aveline says. When they all went to the designated location at the correct time and waited, not surprisingly the flying saucer did not come. Instead of abandoning their beliefs, however, they became even more passionate.

“Because we cannot have two conflicting realities in our minds, we process them and only one becomes dominant,” Aveline says. “So, the cult convinced themselves that the flying saucer did not come because they didn't believe strongly enough. In terms of very strongly held beliefs, evidence against them will, at times, make them even stronger.”

This sort of detachment is very hard to come back from because conspiracy theories become part of a person’s core belief system. To ask someone to stop believing in a conspiracy theory is to ask them to stop being who they are.

It’s important to recognize that “knowledge,” or “truth,” doesn’t have much to do with conspiracy theories, says Dr. Karim Dharamsi, PhD, philosophy professor and chair of the Department of General Education. Conspiracy theories come with specific agendas, such as solidarity, and are built in search of specific outcomes, such as gaining and holding control.

In fact, truth itself has been under debate. “In the late modern period there has been an especially aggressive skepticism about the nature of truth and who gets to make claims about what constitutes knowledge,” Dharamsi says. This is what is known as the post-truth era. “We started to adopt this language that knowledge itself is a construct of some kind that comes out of social practices, linguistic practices and the kinds of endorsements we give each other.”

In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries declared "post-truth" as its word of the year, an “adjective defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’" The “truth decay” is also used to describe the post-truth era, which Dharamsi warns is having an impact on social, political and economic values by elevating self-interest above all else.

“Donald Trump can stand up and make claims about the world, in fact, even make claims that seem patently untrue to some of us, but that affect some kind of energetic shift in the electorate. They privilege that political rhetoric above the claims of scientists, mathematicians and academic experts from all disciplines, because the nature of truth is thought to be an extension of one's desired outcomes or preferences, or political interests. The scientist or the mathematician, or even the philosopher, are at a disadvantage," Dharamsi says.

“Conspiracies attempt to shape public opinion for reasons that have less to do with whether the evidence is justified than with the political outcomes their purveyors have in mind.”

Dharamsi and his colleagues recently completed their second liberal education collection, Between Truth and Falsity: Liberal Education and the Arts of Discernment , which attempts to reveal whether an education of a particular kind allows for a better ability to differentiate between truth and falsehood.

“It's not easy to do that, because the social and political effects of what we endorse sometimes guide the judgments we're making above and beyond our education,” Dharamsi says, providing the example of someone who believes what is best for the economy is therefore best for everyone.

A liberal education does offer the ability to see nuance and understand intersectionalities, building armour against conspiracy theories, but the post-truth era is still problematic.

“If you live in a post-truth era, it's hard to figure out what your point is,” Dharamsi says.

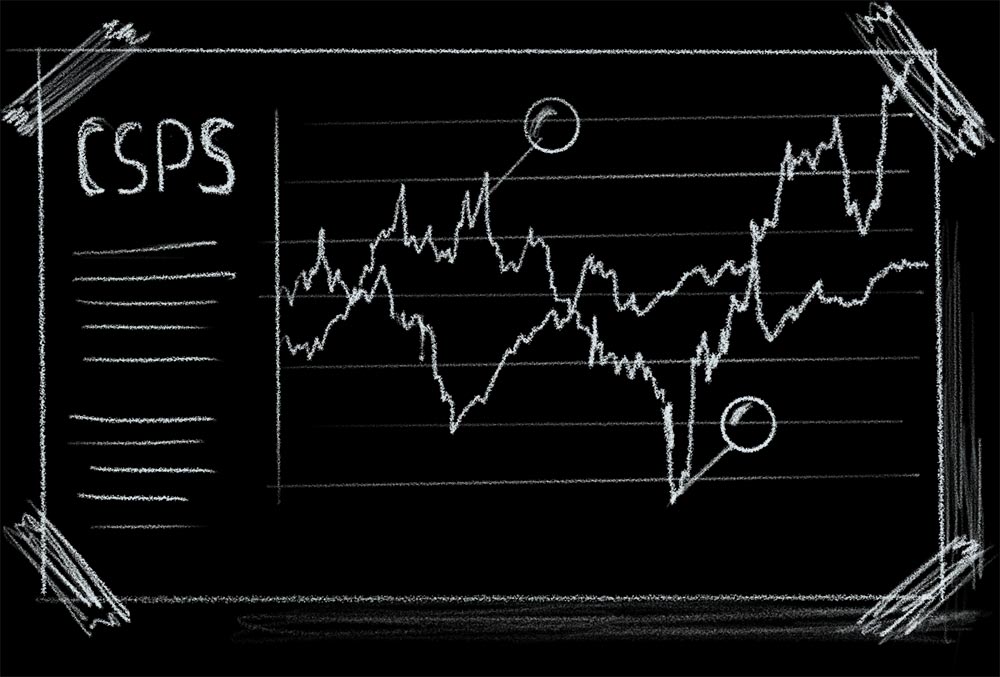

Canadians are not immune to the melee of misinformation — often called an “infodemic” — witnessed south of the border for the past four years. The first of a five-part series of studies out of Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication looking at issues related to COVID-19 titled “ Part 1: Conspiracies and Misinformation Spreading Online” found that a year ago, 46 per cent of Canadians believed in at least one out of four COVID-19-related conspiracy theories. An average of 26 per cent said that they believed COVID-19 was engineered in China as a bioweapon. Nationwide, 11 per cent believed that COVID-19 is not serious, but instead was created to cover up the so-called harmful effects of 5G wireless technology. Twenty-three per cent believed the Trump-led myth that hydroxychloroquine is an effective treatment against COVID-19, and 17 per cent thought that rinsing regularly with saline will protect against the virus.

Part of the study’s research team is Carleton’s Dr. Chris Waddell, PhD, professor emeritus, who is a frequent writing partner of Mount Royal’s Ralph Klein Chair in Media Studies, Dr. David Taras, PhD. The pair most recently co-authored The End of the CBC? in 2020.

Although partisan politicians have made the media an enemy of the people, with Trump showing unguarded contempt for members of the White House press corps and repeatedly using the words “fake news,” Waddell and Taras say trust in Canadian media remains high. In July 2020, 47 per cent of Canadians consumed news every day, says Waddell in his paper, “Canadians, their media, and COVID-19.” His research team noted a “generally positive view of news coverage,” with about 80 per cent of respondents saying that local news media were doing a very good or good job covering the pandemic.

“There's big differences between Canada and the United States,” Taras says. “The numbers that we see out of the United States in terms of distrust of the media are very high and growing.”

A Pew Research Center study from January 2018 backs this assertion up. After surveying 38 different countries, researchers found that the U.S scored the lowest by far when asked if their country’s news organizations were doing well at reporting different positions on political issues. Conversely, only 21 per cent of those who supported the governing party at the time of the survey said their media were doing a good job, while 55 per cent of those who did not support the governing party did. In Canada, those numbers were 82 and 58 per cent, respectively.

“I don't think we're captivated the way Americans are by differences and partisanship and extremist positions. I think Canadians are much more conciliatory, much more trying to understand the other person, and much more trusting of political elites and also trusting of the news media,” Taras says.

When it comes to something as serious as a pandemic, the dissemination of the most accurate information is especially critical.

“Certainly I think one thing that we've learned from this tremendous crisis — this deadly dangerous crisis that we're in — is that there can't be room for falsehood. That you can't allow people to peddle lies that are dangerous to people's lives,” Taras says. He believes that there is a legitimate crisis of the media right now, which is placing democracy itself in danger.

"Media outlets are in a lot of jeopardy and I think they need to be bolstered as major institutions. Whether Canadians are willing to do that, I don't know," he says.

Ultimately, a re-investment in the media, both intellectually and monetarily, will allow it to regain the public's confidence. Society must also work to re-enfranchise people, improve self-worth and reduce "otherness." And it's up to individuals to use tools such as social media responsibly. All will help ease the grip conspiracies currently have on the collective consciousness, and provide the necessary clarity, compassion and constraint in communication.

More notable conspiracy theories throughout history

Nero burned down Rome.

Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Area 51 is a centre for research and experimentation on aliens and their spacecraft.

AIDS was created by the CIA to eliminate homosexuals and African Americans.

Vaccines cause autism.

Chemtrails from aircraft are poisoning populations.

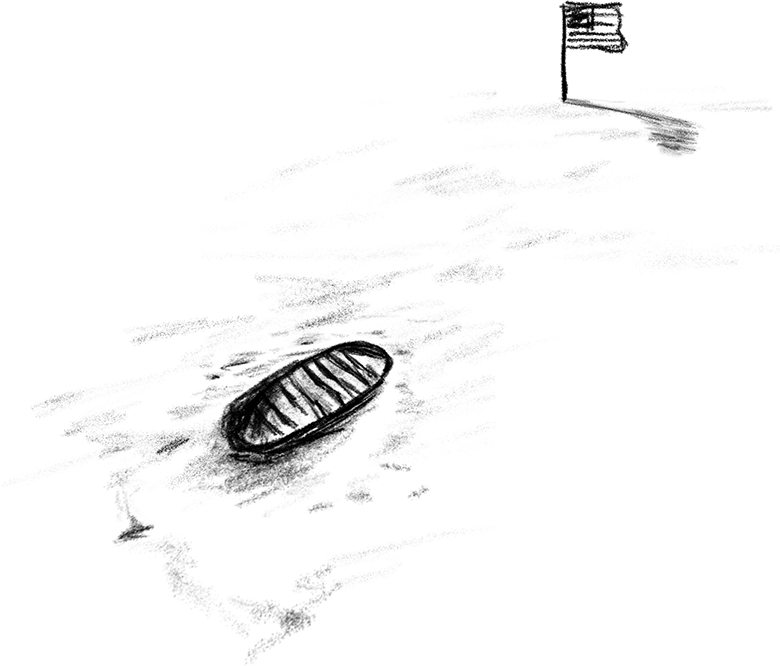

The moon landings were faked.

The Lindbergh baby is alive. And so is Tupac. And maybe even Elvis.

9/11 was an inside job.

Princess Diana’s death was planned by the Royal Family.

The earth is actually flat.

Read more Summit

Is that me?

Impostor syndrome can be debilitating and debassing. Knowing what it is, however, means something can be done about it.

READ MORE