The

resilience

of an

arts degree

Studying the human condition is more important than ever

Being overspecialized can be a major detriment these days for people looking to grow in their careers, says John Lacey, PhD, who received an honorary Bachelor of Arts — Policy Studies in 2018. In his address to Faculty of Arts graduates, Lacey, who worked in energy exploration, production, transportation and marketing around the world, said, “My personal view is that the world today actually needs generalists rather than specialists. People who not only know the field they graduated in, but have developed a knowledge of associated activities so they can assist and advise on the entire scope of projects.”

Lacey’s comment was welcomed in a room full of graduates who likely fielded the “What are you going to do with your degree?” question at least a few times. But, in fact, experts are saying that liberal arts degrees provide a much-needed educational foundation that is increasingly important in all fields.

It’s often said that society cannot move forward if the past is not fully understood, and it’s arts grads who are trained in and are able to apply this type of knowledge.

Inserting morality into the future

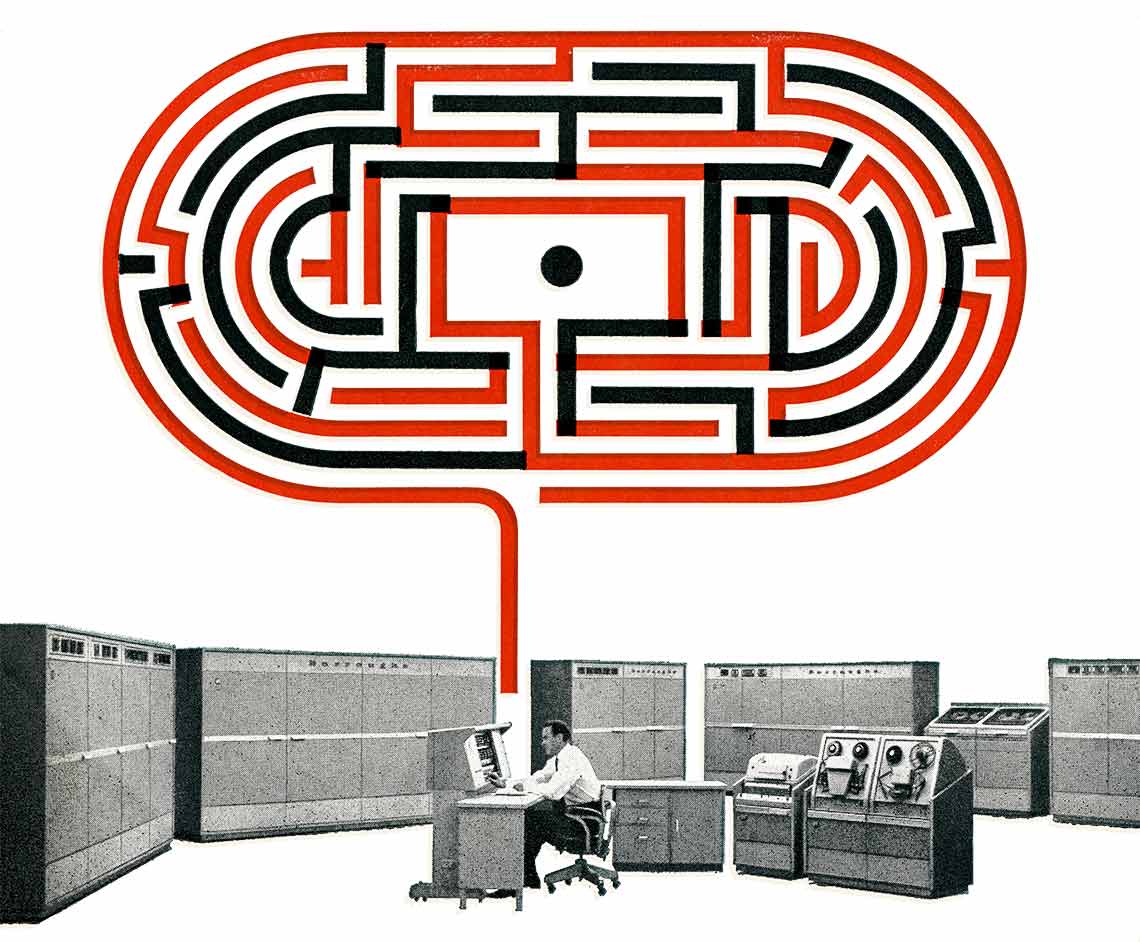

Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom predicts that scientists may awaken the full power of artificial intelligence (AI) in this century. In a 2015 TED Talk, Bostrom suggested that society will eventually reach a point where machine intelligence is the last invention of humanity. Once machines can design themselves, an intelligence explosion will surpass human genius. The machines will never stop learning.

James Stauch, director of the Institute for Community Prosperity at MRU, says there is a steady advance towards the future Bostrom describes. And it’s concerning because it could mean a total loss of control.

“We’re already at the point where there’s machine learning — meaning machines are teaching themselves without the assistance of additional programming,” Stauch says. One example is AlphaGo Zero, a Google-developed supercomputer that uses its experience to keep improving at playing the board game Go.

This will have profound implications. To prevent AI from behaving like the cyborgs in The Terminator, Bostrom says machines must be designed to share our values of right and wrong. There will be different stages of AI learning, so there is time for humans to influence how AI sees and responds to the world.

“The question becomes, what conditions are we putting on raising this early generation of AI?” Stauch says. “So that when it’s an adult, it’s not a psychopath and it won’t turn on us. It won’t be out of our control. And if it is out of our control, at least it’s been taught the right manners.

Just as a parent teaches a child what’s right or wrong, humans must also be diligent in developing ethical behaviour in machines. “I think arts absolutely has a future. Its future is golden if anything,” Stauch says. In a paper titled, “In Search of the Altruithm: AI and the Future of Social Good,” Stauch and co-authors Alina Turner, PhD, and Camilo Camacho Escamilla argue, “AI can be made to be generative, beautiful and not merely ethical, but rationally compassionate and just, enriching our lives beyond what we can currently imagine.”

Social issues that could be (finally) successfully addressed include homelessness, diseases and even war and violence, the authors argue.

The problem solvers

Liberal arts majors are perfectly positioned to tackle the most complex and pressing issues of our time, says Nancy Ogden, PhD and chair of the Department of Psychology at Mount Royal.

“Our world is changing so rapidly that there’s an advantage to an arts degree. Our arts students are exposed to a variety of views and they learn to think critically about those views. In this increasingly divisive, rigid time, I think that’s a particularly useful skill.”

There are, in fact, no “arts-less” programs at MRU. All baccalaureates require that up to 25 per cent of course loads consist of general education classes, which are based around four thematic clusters: communication; community and society; values, belief and identity; and numeracy and scientific literacy.

General education courses ensure students receive a deeper education and are able to assess and communicate their knowledge of the world around them.

Humanity may be winning

While there have been changes in recent decades requiring an increased demand for computer skills, the jobs that are least likely to be automated involve liberal arts skills, says Jennifer Pettit, PhD, dean of the Faculty of Arts.

According to a 2016 report from the McKinsey Global Institute, the hardest activities to automate with the technologies available today are those involving managing and developing people (nine per cent automation potential); where expertise is applied to decision-making, planning or creative work (18 per cent); and interacting with customers, suppliers and other stakeholders (20 per cent).

“It is no longer realistic to think that students obtain everything they need for success from a narrow, traditional degree,” Pettit says. “Rather, employers are eager for their workers to learn what are sometimes deemed ‘soft skills.’ ”

The Washington Post reported in 2017 that the top characteristics of success at Google are communication, empathy, critical thinking, problem solving and creativity, all of which Pettit says are developed and nurtured through the Faculty of Arts.

Arts and humanities courses are where discussions of values and responsibility generally happen, and from that a society’s moral foundation is established. For example, laws are not created and punishment not decided upon without vigorous debate.

Duane Bratt, PhD, chair of the Department of Economics, Justice and Policy Studies, says, “Criminal justice has existed since the beginning of time. Our grads study what causes crime? How to prevent crime? How to deal with criminals?” As long as there are humans on the planet, Bratt says, crime will exist, but it can be curtailed through the study of criminality and dealt with through the study of justice.

Standing out in the workforce

Michelle Cook is a career and education counsellor at MRU who works closely with Bachelor of Arts (BA) students to support them in their career planning. She says, “BA students are well-rounded and adaptable — traits that prepare them for many types of careers.”

Some of the skills BA grads possess that today’s employers want include global and intercultural fluency, and teamwork and collaboration. They are also able to spot patterns and relationships among diverse groups, providing them with a competitive edge and balance in the workplace.

“Arts degrees instil curiosity, literacy and empathy in grads — skills that are difficult to quantify or measure, but ones that are critical to helping organizations solve problems and to long-term career success,” Cook says. BA graduates are adaptable and responsive, respectfully exploring topics and critically assessing and analyzing information, all while building their knowledge of cultural and global perspectives.

“Our rapidly changing and advancing world means that employers want employees who can quickly navigate those changes and keep up with them.”

Sociology on a global scale

Melanie Putic graduated with a Bachelor of Arts — Sociology in 2014 from MRU, moving on to obtain a Master of Arts from the University for Peace in environment, sustainable development and peace. Her career has taken her from the United Nations in New York to the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, D.C. She says her undergraduate degree from Mount Royal set her up for success by impacting her worldview toward a much more in-depth, wide-ranging and multidimensional way of thinking. Her understanding of societal issues today, she says, “is well-founded, well-informed and oriented towards solutions with real potential.”

Vivek Wadhwa is a tech entrepreneur who argues liberal arts and the humanities are as important as engineering in a column published in The Washington Post. His reasoning that, “Tackling today’s biggest social and technological challenges requires the ability to think critically about their human context,” resonates with Putic.

“A critical thinking and human context approach is vital for sustainable solutions. This was a key theme throughout my degree. Ideas and initiatives can only become sustainable solutions if they have been put through a complete thinking process that considers possible outcomes, potential problems and impacts on people and the environment. It is these kinds of solutions that we need in the world today,” Putic says.

As the world becomes more and more interconnected and automated, Putic says she is able to sort through the ever-growing amount of information available and properly put into perspective new problems that arise.

Mount Royal’s arts departments: Why they matter

The Faculty of Arts grants eight degrees, the most out of all five faculties, plus has more than 20 minors. Students can graduate with a bachelor’s in anthropology, criminal justice, English, history, policy studies, psychology and sociology. We asked department chairs why the world needs their graduates. Here are their perspectives.

Duane Bratt, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Economics, Justice and Policy Studies

“We often think of public policy, but within all organizations — public, private and non-profit — there are an array of policies — hiring policies, human rights policies, various types of internal processes and regulations. Our grads are skilled at dissecting, developing and disseminating this type of information.

“The criminal justice program dives into the criminal justice system, crisis and conflict resolution, human rights and the social science of criminology. All of this makes students highly employable in fields such as social justice, criminology, law, police services and more.”

Tom Buchanan, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology

“Our students possess an understanding of inequality and intercultural sensitivities, and are well-prepared and motivated to work in cross-cultural, international settings. The analytical and critical perspectives of anthropology and sociology graduates will increasingly contribute to the betterment of organizations, governments and societies for years to come.”

Mark Gardiner, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Humanities

“We desperately need those who can ask and answer probing questions about the causes, directions, and consequences of change — who can ask, for example, whether an increasingly automated society is, in fact, one that we want. Who benefits? Who is left behind? What social systems do we need to put in place to protect or accelerate the good and to mitigate the harm? These types of self-reflective critical questions, deeply intertwined with the sort of concepts that are difficult to place in the sciences, like the good and the just, are precisely what the history major and humanities are designed to ask and answer.”

David Hyttenrauch, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of English, Languages and Cultures

“English graduates carry with them a range of skills: analysis, critique and communication. They are well-versed in a range of communication styles, and thoughtful about the ways particular communications approaches influence others. Skilled communicators are always in demand, and they make skilled leaders and practitioners in any field. These skills are employable ones, true, but they’re also essential qualities of engaged citizens, and our graduates will be members of many communities — social, economic and personal — over their lives.”

Jennifer Pettit, PhD, professor and dean of the Faculty of Arts

“The liberal arts are key to solving what some are now calling the ‘wicked problems’ of our time, ones that have no clear answer and that have numerous, interdisciplinary causes. At MRU, this means more exposure to a wider variety of disciplines through programs such as general education, in which liberal arts disciplines are core. Given how rapidly society is changing, a strong case can be made for breadth over specificity.”

Arts employability stats

Mount Royal University’s work-ready arts graduates quickly enter their career fields, as these numbers from the Government of Alberta’s 2018 Graduate Outcomes Survey suggest. Bachelor’s degrees continue to be valuable for all alumni, as well. Statistics Canada’s 2018 National Graduates Survey (class of 2015) reports that 90 per cent of Alberta’s graduates were employed three years after completing their studies.

Data from the Government of Alberta’s 2018 Graduate Outcomes Survey

83%

of art grads were employed within two years after graduation 1

of those employed... 2

88%

work full time (30 hours or more per week)

89%

hold jobs related to the general skills and abilities acquired at their institution

1 Based on those in the labour force, for example, excludes those enrolled as a full-time student and those who said they were not employed and not looking for work.

2 Percentages are based on those who said they were employed. Follow-up questions about employment asked graduates in reference to their main job — the job in which they worked the most hours if they had more than one.

Prepared by: Institutional Analysis and Planning of Mount Royal University

Read more Summit

Journalism: Decelerated

A return to in-depth, investigative storytelling.

READ MORE