Indigitization project preserves Indigenous knowledge and culture

— Mount Royal University | Posted: October 3, 2022

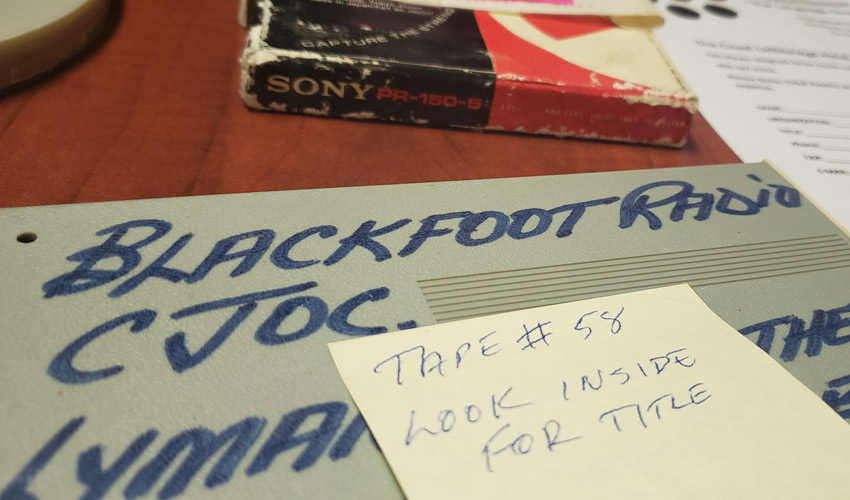

Anthropology and Indigenous studies liaison librarian Jessie Loyer poses with a digitization kit.

Indigenous communities often possess invaluble audio recordings that document language and culturally significant practices. These recordings are critical to each community as they serve as a conduit for conveying tradition to future generations.

The recordings are typically found on cassette tape and as the recording format ages it is more important than ever to digitize the content.

In 2010, the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology (UBC MOA) initiated a project to empower Indigenous communities to collect and preserve their analog recordings. Through an endowment, UBC MOA distributed grants to communities, loaned equipment and trained people to begin a digitization process. The project was named Indigitization.

“I've always thought this was a really great initiative, and after a visit to the Piikani Elders Lodge in 2016 where elders mentioned how many cassette tapes they had, I looked for a way we could bring the project to Mount Royal University,” says Jessie Loyer, anthropology and Indigenous studies liaison librarian at MRU.

At the time, funding allocated for Indigitization was restricted to the province of B.C. However, when a private donor approached the office of indigenization and decolonization (OAI) with a gift to be used for an “Indigenous initiative,” Loyer saw an opportunity to bring Indigitization to the University.

“I suggested we bring the project to Alberta to purchase cassette tape digitization kits and provide training to communities here in Treaty 7,” explains Loyer.

The collaborative work to bring Indigitization training to MRU involved members from the OAI, the Library and the MRU Foundation.

Collaborative training

Participants from the Blackfoot Confederacy, MRU and Red Crow Community College completed intensive digitization training with Gerry Lawson, coordinator, oral history and language lab at UBC MOA. In advance of the training, the Library purchased two cassette digitization kits using the specifications provided by Lawson, which were used in the training and are now available for loan.

Gerry Lawson explains the digitization process.

“Libraries can play an important role in the ongoing work of Indigenous reconciliation and supporting this project aligns with MRU’s commitments to address a legacy of broken promises, exclusion and colonization,” says Meagan Bowler, dean of the MRU Library.

“Libraries are committed to ensuring that knowledge is accessible and available widely; but we also acknowledge that historically, Libraries have excluded Indigenous voices and perspectives in that work.”

Finished recordings

Many digitization projects are available to the public, which is generally good. Indigitization takes a different approach because some aspects of Indigenous knowledge details protocols on how and when that knowledge can be shared.

For example, “certain Cree stories are only told when there is snow on the ground,” explains Loyer.

“Community members decide what they want to do with their digitized files and are not required to place a copy with MRU, although we're happy to accept a copy if that's what they would prefer.”

Indigitization is important because it allows the community to digitize their own knowledge, within the protocols that make sense for them, and allows for digital sovereignty.

Recordings are typically found on cassette tape and as the recording format ages it is more important than ever to digitize the content.

dr. linda manyguns, phd, MRU’s associate vice-president of indigenization and decolonization, says Indigitization is a critically important project that enables independence and builds skills.

“These recordings could assist in cultural revival, personal knowledge or relate historical memories held in stories.”

For Loyer, a personal connection was integrated into Indigitization training.

“We used my grandfather's tapes as training tapes.”

The recordings belonged to Loyer’s grandfather, Gilbert Anderson, who was an old-time Métis fiddler champion. Though he was well-known, Anderson never produced a professional album, so it is challenging to find his music online. One video is available on YouTube.

“His tape was digitized and now my mom can share that music directly with younger fiddlers like Zachary Willier,” explains Loyer.

Watch the 4-minute Indigitization program video.