'You cannot, and must not, be satisfied with easy answers'

When he’s not exposing his students to new cultures and ways of thinking, Assistant Professor Ademola Adesola, PhD, is busy deconstructing the postcolonial narratives that are often default in the Western world. And he has a new book out doing just that.

Adesola has been teaching for nearly two decades and joined MRU’s Department of English, Languages, and Cultures in 2022. He’s taught a variety of courses, but the ones he finds most interesting — he stops short of picking a “favourite” — are the first-year classes.

“They are the foundation of the English program. Those are the courses through which you help those predominantly fresh-from-high-school students transition into the core of university learning,” he says.

“The challenge at this level is to activate the spark of interest in the sheer joy of learning.”

Outside of fanning the flames of learning, he hopes to impart two big lessons.

One: Ask questions.

“I always want my students to be comfortable with asking difficult questions,” he explains, adding that asking tough questions is essential to understanding the world around them.

“I demonstrate this by asking them questions and questioning their responses. Questioning those answers helps to drive home the point that they cannot and must not be satisfied with easy answers.”

Two: “Different” is not synonymous with “bad.”

“My students need not be discomfited by differences. They must accept the fact of the differences of peoples — whether those are race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, culture, family background, and any other markers of human differences,” he shares.

“Differences are not diseases. They are important elements of who we are.”

Chair of the Department of English, Languages and Cultures Rob Boschman, PhD, calls Adesola’s presence at MRU invaluable.

“He’s the most engaged colleague, perhaps, that I work with. He's involved in so much, especially to do with equity, diversion and inclusion. Very much a community organizer, and he works very closely with students and with faculty and administration.”

Differences in the portrayal of child soldiers

When the metaphorical bell rings and class is dismissed, Adesola practices what he preaches, researching and writing on a subject that has fascinated him: child soldiers.

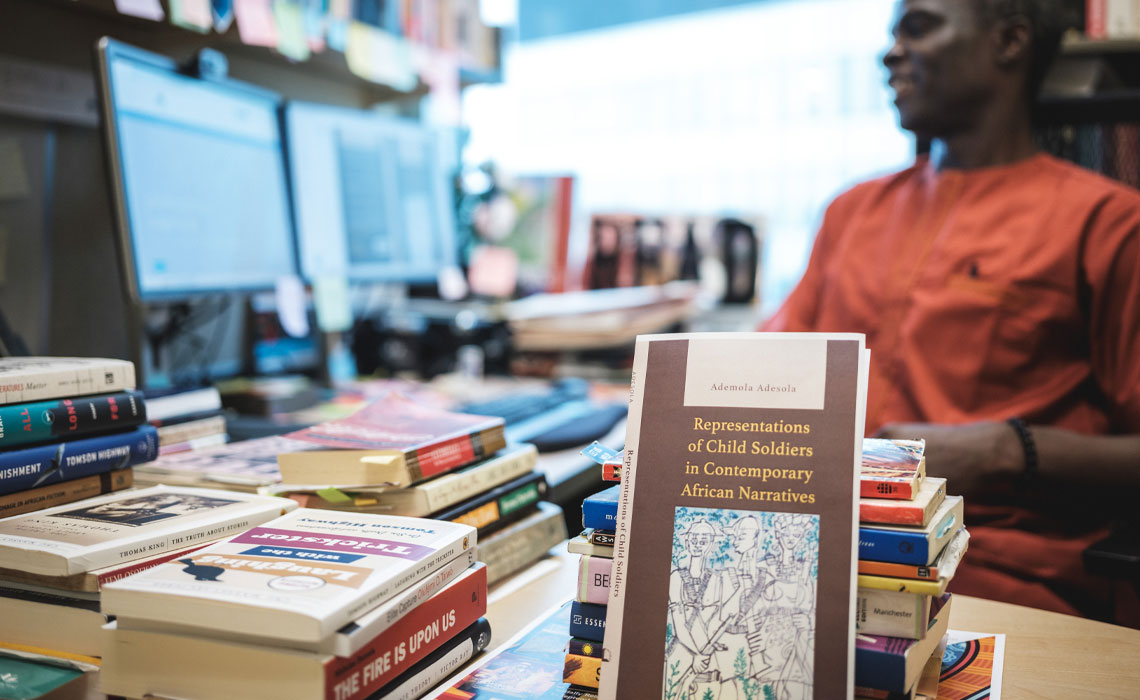

His new book, titled Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives, was published this month. Boschman calls it “a really significant and unique piece of work.”

“I chose this subject because I wanted to understand the forces and discourses informing how we make sense of child soldiering and war in African contexts,” Adesola says.

Adesola has studied this subject extensively, hosting conference presentations and writing journal articles that explore child soldiers from different angles.

“I have done a comparative reading of novels that depict Jewish child soldiers during the Holocaust and African child soldiers. Why is the Jewish child soldier positively imagined and their African counterpart pejoratively portrayed?”

He also notes that in most portrayals, the young fighters are boys, while in actuality girls are no strangers to battlefields as well. Adesola points to another glaring bias — that youth violence exists only in underdeveloped societies.

“Representations cannot exclude those children who wield guns in the U.S. and knives in Britain. For example, schools in the U.S. are fast becoming militarized zones because of gun violence.”

He delves further into biases in the representations of child soldiers in his book:

“Notable too is the fact that Western publishers of these stories are deeply aware of the immeasurably significant emotional impression that book front covers, especially those depicting the vulnerability of children, have on the reading public. I submit that front cover designs of African child soldier narratives, considered as paratexts, are sites filled with tensions and contestations since what is represented in cover designs can sometimes depart dramatically from what the book is actually about. […] Thus, the paratextual condition of African child soldier narratives is marked by tension, ambivalence, misinformation, discrepancy, and stereotype.”

His book challenges its readers to reconsider their preconceived notions about children being fundamentally vulnerable and irrational.

“Children, generally, are not humans without some capacity for actions. Children at war and those impacted by it, or even those caught in the throes of poverty, penury and economic hardship, do not just sit on their hands and do nothing. They act,” he says.

“Childhood is not a disability.”

Humanitarian organizations’ rehabilitation programs tend to focus on victimhood and ignore the pre-war realities that stripped children of their innocence well before they were given a gun.

“That loss [of innocence] started with their experiences of deprivation, political violence/instability, kidnapping, domestic abuse, and sexual violence in supposedly peacetime. It is what was left of that innocence at the point of enlistment that involvement in the armed group finished off.”

Adesola says aid groups that sidestep the core of the issue will only produce “young humans who are recyclable tools for another war.

“[Child soldiers’] survival strategies need to be studied. Their understanding of conflicts matters. The different identities they have forged and the responsibilities they have taken on are important… A one-sided understanding of child soldiers as innocent victims of adults’ devices cannot yield meaningful insights.”

Value casts a wide berth

Adesola emphasizes that “both the readership and the market of the book are wide and encompassing.”

Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives is applicable material for scholars and students (in Africa, North America, Asia, and Europe) interested in child soldier narratives, African and Black diaspora literatures, childhood studies, African studies, post-colonial literatures, human rights, peace and conflict studies, African history, as well as non-academic audiences interested in recreated accounts of children and war in African contexts.

“The book can be used in courses focusing on children and warfare, literature and war, peace and conflict, issues in postcolonial literatures, special topics in global literatures, African studies, African diaspora literatures, trauma and violence, comparative examinations of depictions of women and girls in African literature, and literature and human rights,” Adesola says.

“And, as I say in the concluding part of the book regarding films on African child soldiers, ‘I hope, too, that Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives stirs more interest in this direction, as well as in the new narratives on children and warfare that are sure to be authored in times to come.’ ”

Representations of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Narratives is available on Amazon and Rowman.