Cretaceous Seas and Lands Exhibit

Installed in the atrium and the ceilings in Mount Royal's East Gate and B-Wing, Cretaceous Seas and Lands provides students and the public the opportunity to view life-sized specimens of extinct dinosaurs, marine reptiles and fishes that swam or flew the across western North America during the Cretaceous Period, more than 65 million years ago. The casts on display were constructed from molds produced from bones of dinosaurs, marine reptiles, pterosaurs and fishes unearthed from sea bottom muds deposited in the Western Interior Seaway.

Cretaceous Seas is the largest marine vertebrate exhibit in Calgary.

What is the Cretaceous Period?

The Cretaceous Period (144-65 million years ago), the final interval of the Mesozoic Era, ended about 64 million years before the first humans evolved. Several times during the Late Cretaceous, sea level rose, flooding extensive areas of continents including the interior of North America. During the Cretaceous Period, pressures from oceanic plates plunging below North America crumpled the western margin to produce the Cordilleran Mountains. But, further eastward, the continent warped downward. The result was the incursion of marine waters into the continent's interior to produce the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow watermass (< 200 m deep) that for much of its history extended from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean.

Much of Alberta was covered by marine waters during mid to Late Cretaceous time. In these mild to cool temperate waters, predatory marine reptiles including mosasaurs, plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs flourished. Nearly complete skeletons of marine reptiles are known from southern Alberta and near Fort McMurray where Cretaceous marine strata are exposed.

The rise of the mountain ranges along the western edge of North America intensified during the Cretaceous Period. From these highlands, river systems carried vast quantities of sediment eastward into Alberta where it accumulated in thick layers now exposed by erosion in valleys and badlands through much of the province. Swampy, subtropical, coastal lowlands supported forests of conifers, cycads, ginkgoes and early flowering plants. The lush vegetation served diverse plant-eating dinosaurs that, in turn, were prey for fearsome predators.

On Display

Pteranodon

Pteranodon

The flying reptile Pteranodon (twice the size of the largest living flying birds) is the most common pterosaur in Upper Cretaceous sediments of the Western Interior Seaway of North America, with about 1,200 specimens recovered to date. So far though, none is known from Canada, the most northerly records coming from North Dakota.

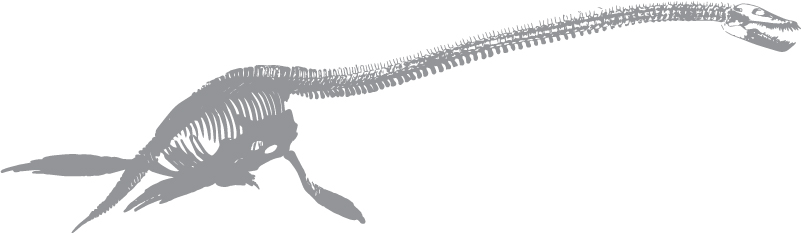

Elasmosaurus

Elasmosaurus

With more vertebrae than any other known animal, the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus developed a remarkably long neck that supported a small snake-like head. The short tail suggests Elasmosaurus was a slow swimmer that relied on large flippers powered by massive swimming muscles inserting on heavy ventral bones. The neck could be retracted into a shallow, lateral, sigmoidal curve enabling a snake-like retraction and strike to capture fishes and cephalopods.

Enchodus

Enchodus

Enchodus is an extinct genus of bony fish that flourished during the Late Cretaceous with a near global distribution. An important member of Cretaceous marine food webs, Enchodus avoided the mass extinction at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived another 20 million years, well into the Cenozoic Era.

While more closely related to salmon and trout than herring, Enchodus earns its nickname, the "sabre-toothed herring," from the prominent fangs at the front of its jaws. Formidable teeth, together with a sleek body and large eyes, indicate Enchodus was an active predator. But, Enchodus too was sometimes prey. Its remains have been recovered from stomach contents of other Cretaceous predators including mosasaurs, sharks, plesiosaurs and seabirds.

![]() Platecarpus

Platecarpus

Platecarpus, like other mosasaurs, was an aquatic lizard-like reptile that shows remarkable adaptations for a seafaring life. The downturned tail supported a crescent-shaped tail fluke. With flipper-like limbs for steering, the tail likely propelled the animal with a shark-like motion rather than the snake-like undulations proposed by earlier researchers. Preserved gut-contents show mosasaurs feasted mostly on fishes, flightless aquatic birds, and other marine reptiles.

Protostega

Protostega

An extinct genus of marine turtle, Protostega is known from Upper Cretaceous deposits in both Canada and the United States. The cast specimen on display at Mount Royal University is a juvenile. Adults grew to more than three metres in length, with a weight of about two tons, making Protostega one of the largest turtles in Earth history.

Unlike most turtles, the carapace of Protostega is lightly constructed and probably supported a soft shell similar to that of modern leatherback turtles. This lightweight construction, together with powerful front flippers, suggests Protostega was a tireless swimmer. Just as marine turtles do today, females in the Western Interior Seaway likely migrated hundreds of kilometres to lay eggs on sandy beaches.

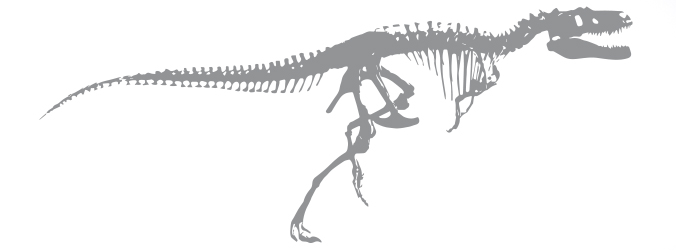

Nanotyrannus lancensis

Nanotyrannus lancensis

Regarded as distinct by some researchers, Nanotyrannus lancensis is thought by others to be a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex. However, the skull bones are fused, suggesting it is indeed an adult, and it has more teeth in the jaws than does T. rex, although this might simply reflect change during growth or individual variation within a population. The dagger-like teeth and comparatively sleek skeleton suggest an agile predator. Multiple individuals of carnivorous dinosaurs found in some bone accumulations is taken as evidence that at least some species hunted in packs.

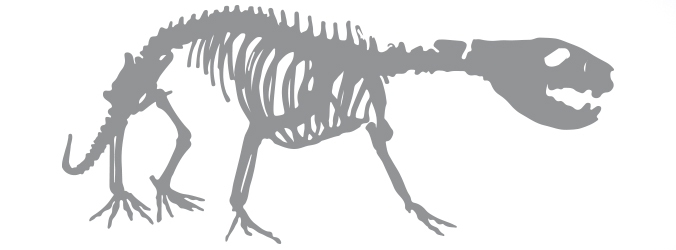

Didelphodon vorax

An early member of the marsupials (pouched mammals), Didelphodon vorax is relatively large for the Cretaceous Period, when most mammals were only mouse- to cat-sized. Abundant fragments occur in Upper Cretaceous strata of western North America, including Alberta, although only a single complete skeleton is known, a cast of which is displayed here. With short heavily constructed jaws and blunt premolar teeth, D. vorax likely crushed bones of small prey such as lizards and frogs or the shells of mollusks. Although most closely related to the opossum among extant mammals, the elongate body and the broad flexible feet indicate D. vorax was probably semi-aquatic like an otter and may have lived in burrows in river banks.

Triceratops horridus

Triceratops horridus

Among the most familiar of dinosaurs, Triceratops was a large, four-legged plant eater that weighed up to 12 tonnes, about twice the weight of an African bush elephant. The skull of adult Triceratops featured a distinctive head shield and three facial horns. The "baby" displayed here was probably between one and three years old. Its horns and frill, though nascent, are developed well before maturity indicating these features in adults were primarily for species recognition and visual communication rather than for sexual display. A contemporary of Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops was among the last of the dinosaurs before mass extinction brought their reign to an end at the close of the Mesozoic Era.

Contact

For more information, please contact the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at 403-440-6615.